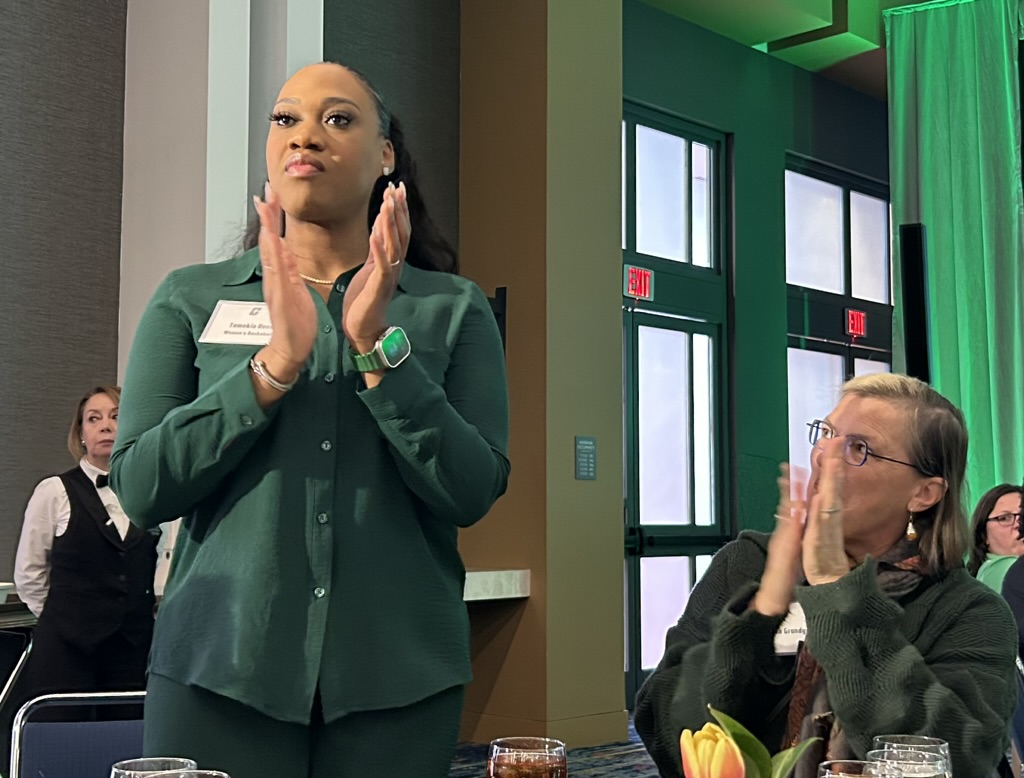

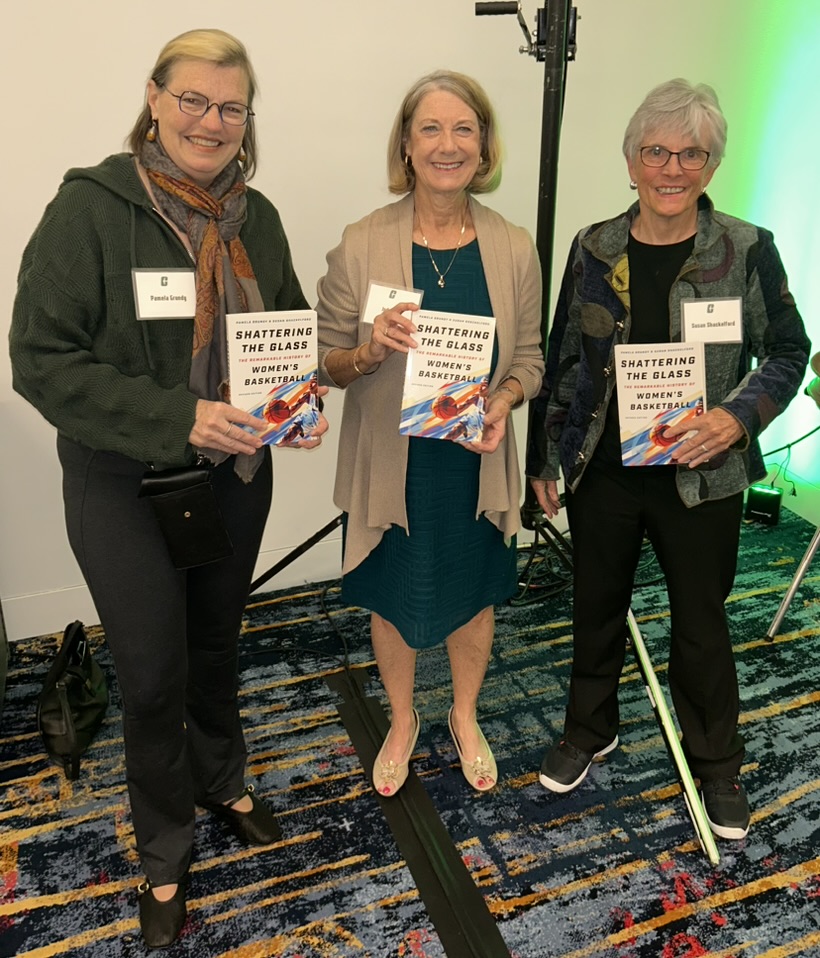

So excited to have Shattering the Glass out in the world!

We’ve been sharing some tidbits on social media – one each day or so. We’re gathering them here. Enjoy! If you like what you see, you’ll find a lot more in the book.

February 2: The Meaning of Sports for Women

In the late nineteenth century, the United States became an increasingly urban, industrialized nation. Organized team sports, which seemed to mesh neatly with the demands of a competitive industrial society, grew in popularity and significance. College women and men frequently used sporting metaphors to describe the world they were preparing to enter.

“Educated women who seek employment must keep in mind the fact that only by the sweat of the brow is man’s bread won,” Atlanta University’s L.I. Mack wrote in 1900. “They must also remember that if they descend into the arena, they cannot hope for success unless they accept the conditions under which an athlete must strive. They must be prepared for hard work, for persevering work, because the race will be the same for them as for the men. The men will go beside them, struggling for the same prize; and, since men have, in the start, the advantage of the women, they must brace up every energy, and bring into play every faculty, to avoid defeat and ensure victory. Whatsoever they undertake, they must, and will, and do go through with it to the end.”

Players at Hampton University, 1907. Courtesy of the Hampton University Archives.

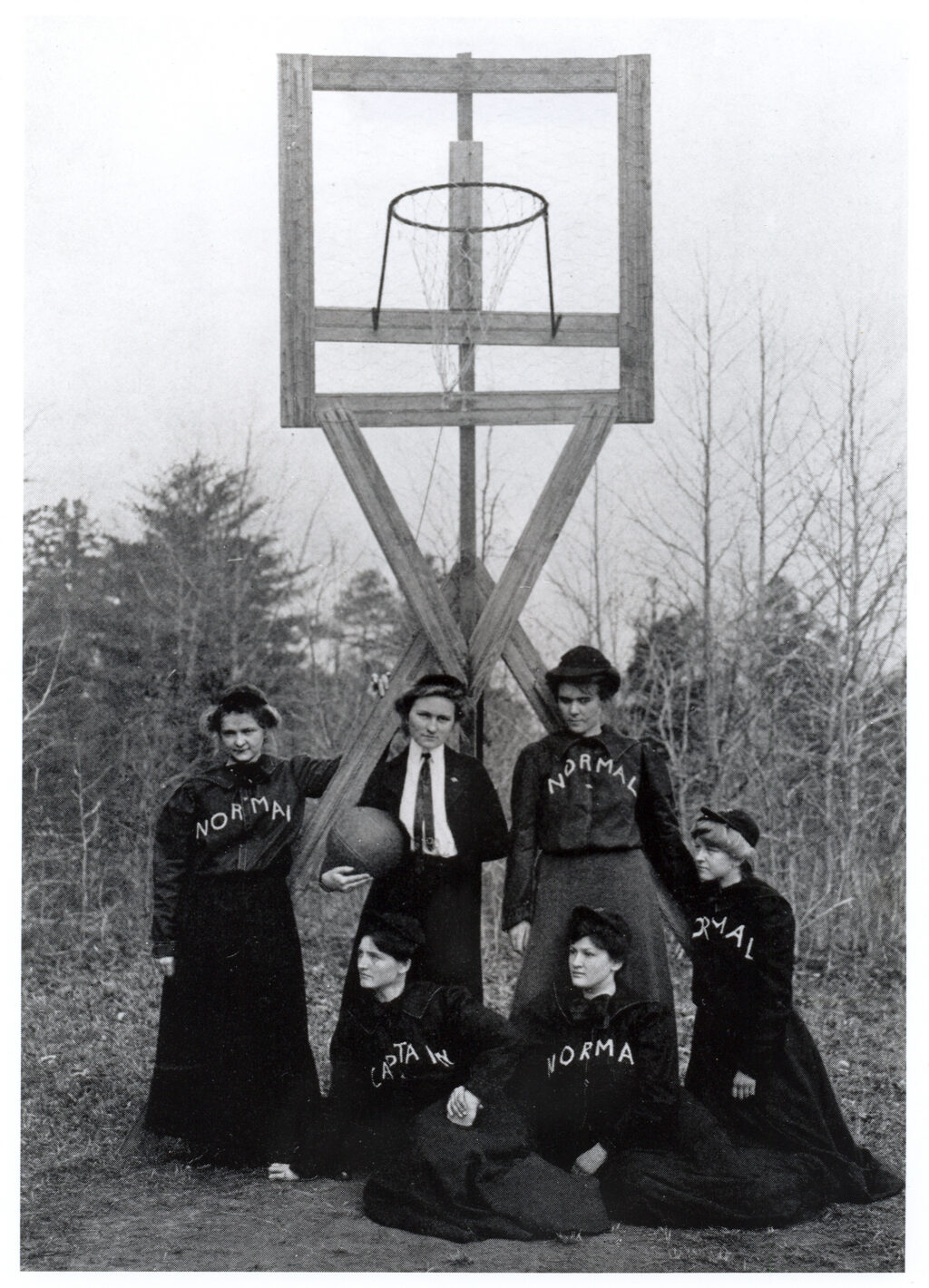

February 4: Early Teams

Most women’s college basketball programs focused on intramural play, with games that pitted one class against another – freshmen against the juniors, sophomores against the seniors and so on. Students, most of whom had little experience with competitive athletics, joined in with enthusiasm.

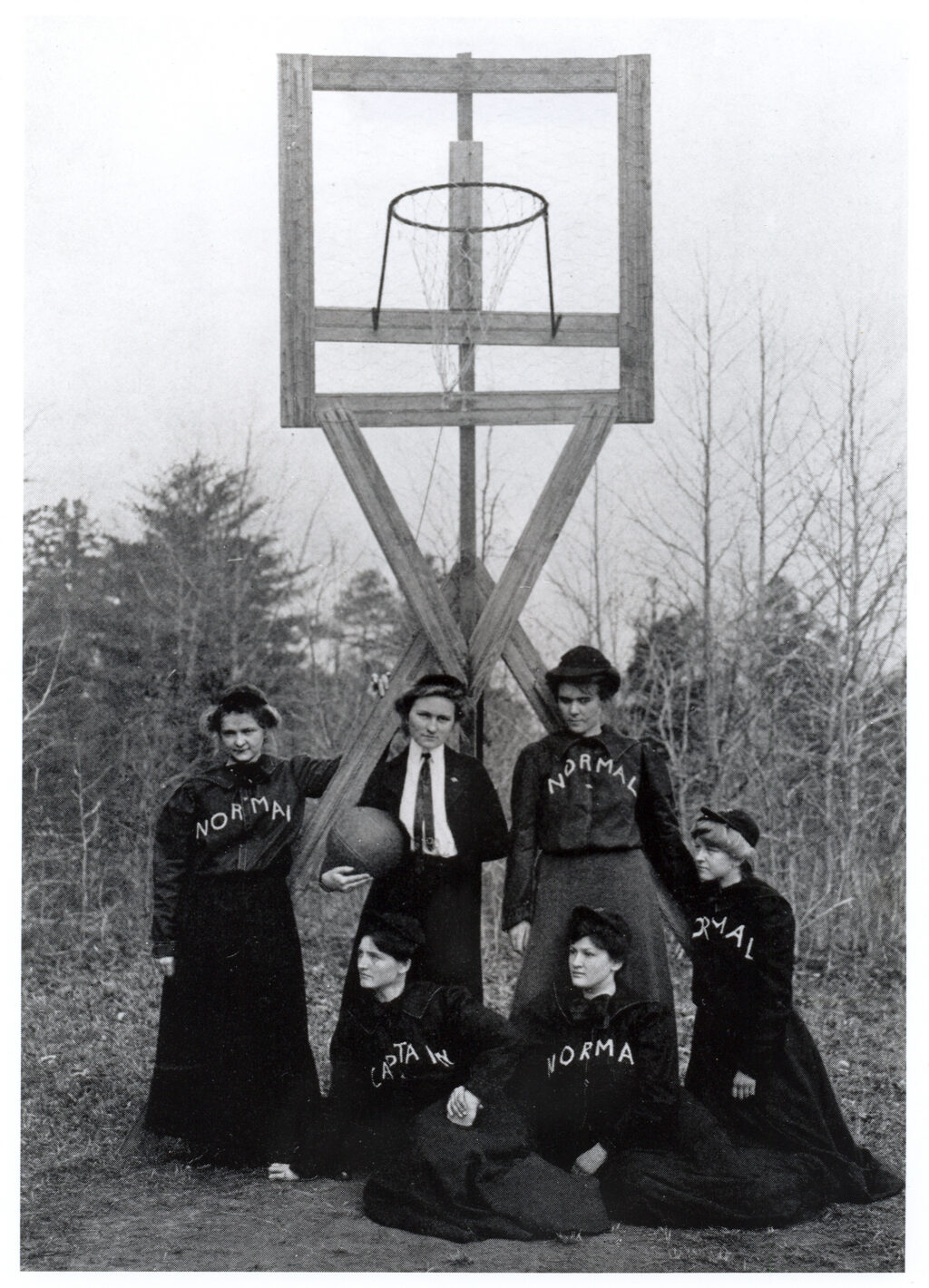

In 1900, students at North Carolina’s State Normal College proudly recounted their athletic gains. “In athletics we are the progenitors of a new regime,” the class of 1900 announced in their summary of class accomplishments. Previously, “the walls of the now elegant library enclosed all our efforts toward physical culture. There we wrestled in the dust with greased poles and dumb-bells, while ‘all outdoors’ remained unnoticed.” But the class had taken action. “The enthusiasm ran so high over basket ball in the spring that a determined few lent themselves to the task of cleaning and preparing the grounds,” they noted. “The athletic spirit spread until now every class in the school plays basket ball . . . .”

Team from State Normal College, Greensboro, N.C., 1900. Courtesy of the University Archives, Jackson Library, University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

February 5: First Women’s Intercollegiate Game

In 1896, basketball teams from Stanford and the University of California met in the nation’s first intercollegiate game, won by Stanford.

The idea of women playing an energetic sport in public was controversial, and men were banned from the San Francisco armory where the game took place. Both of San Francisco’s newspapers filled their pages with descriptions of the game. One assigned its story to Mabel Craft, an aspiring young woman who would later become one of the state’s leading reporters, as well as an outspoken advocate for the rights of women and African Americans.

Craft’s article went straight to the point. Basketball, she wrote, “wasn’t invented for girls, and there isn’t anything effeminate about it. It was made for men to play indoors and it is a game that would send the physician who thinks the feminine organization ‘so delicate,’ into the hysterics he tries so hard to perpetuate.”

Stanford University’s victorious team. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University.

February 6: Charlotte, N.C.’s First Women’s Game

Coverage of Charlotte’s first women’s intercollegiate basketball contest, between Elizabeth and Presbyterian colleges in April of 1907, showcased both the appeal and the controversy surrounding women’s growing interest in athletics. As with many early games, male spectators were barred. When several scaled nearby buildings to see the game, they were arrested. The Charlotte Observer chronicled the action.

“It was exactly 4:30 o’clock when the two teams ran out, greeted by a tumult of cheers and an avalanche of streamers. The players, it is understood on good authority, were attired in abbreviated skirts, that nothing might impede the celerity or the alertness with which they leaped, dived heroically and sped determinedly toward their rivals’ goal. It was a scene such as is not witnessed every day in staid old Charlotte.”

“The only regret in town was that all save women were barred. Had the gates been thrown open the coffers of the athletic clubs of the colleges would be filled with gold, for business would have been suspended and the populace would have turned out en masse.”

Charlotte News cartoon, courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

February 7: Fort Shaw Indian School Team Triumphs

In October of 1904, at the St. Louis World’s Fair, the women’s basketball team from Montana’s Fort Shaw Indian School defeated a Missouri all-star team and claimed the title “World Basket Ball Champions.”

The team proudly bore their trophy home. They left behind a powerful statement about Native American abilities. “To the great surprise of several hundred spectators,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch observed, the Fort Shaw players proved “more active, more accurate and cooler than their opponents.”

You can learn more about the team and players here, and in the book Full Court Press, by Linda Peavy and Ursula Smith.

Photo courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis.

February 8: The Spread of High School Basketball

In the 1920s, as high schools sprang up in a growing number of American communities, basketball teams multiplied. Students loved the game – girls as well as boys. Archives and scrapbooks across the country preserve pictures of countless girls’ high school teams grouped around a ball and looking proudly into the camera.

Many decades later, North Carolina player Lavinia Ardrey Kell summed up the excitement of those early days: “I would love to be young one more time, just to get to play basketball.”

Winchester Avenue team, Monroe, N.C., 1920s. Courtesy of Rosa Rushing.

February 9: Iowa Style

Support for girls’ high school basketball reached a peak in Iowa. When the Iowa High School Athletic Association voted to eliminat the sport, a group of small town coaches rebelled, and formed the Iowa Girls’ High School Athletic Union. They created a state basketball tournament that became a beloved state institution, and girls’ basketball soared past boys’ in popularity.

“Take a tour through the country and you’ll find an old tire rim nailed to the side of a building. These are never rusty. They are kept polished by a constant rain of shots from an aspiring girl and one or two neighbor girls or boys.” – John Schoenfelder, Clutier High School coach, Clutier, Iowa

Ida Grove high school team, Ida Grove, Iowa. Reproduced, with permission, from the Collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Library.

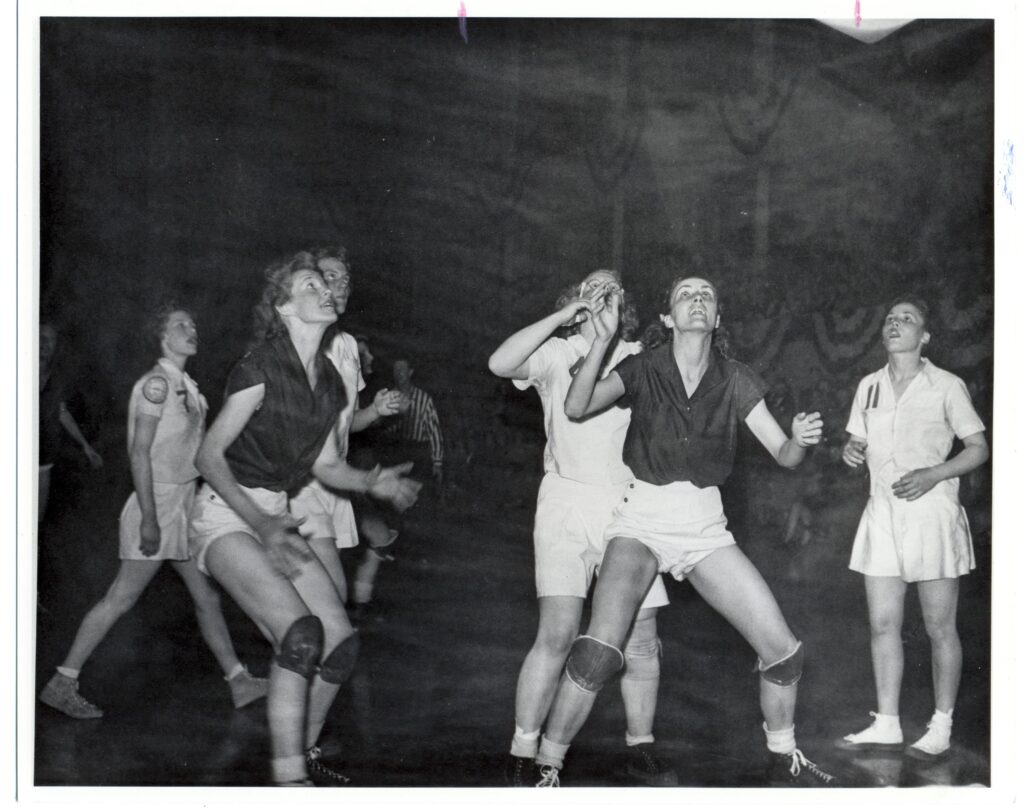

February 10: Bennett College

In the 1920s and 1930s, a number of Black colleges sponsored competitive women’s basketball teams. The many social, political and economic challenges faced by Black communities meant that Black women were used to engaging in a broad range of activities. Neither administrators nor students saw contradictions between competitive sports and ladylike refinement.

“We were ladies,” explained Bennett player Ruth Glover. “We just played basketball like boys.”

Photo courtesy of the Heritage Hall Archives and Research Center, Bennett College.

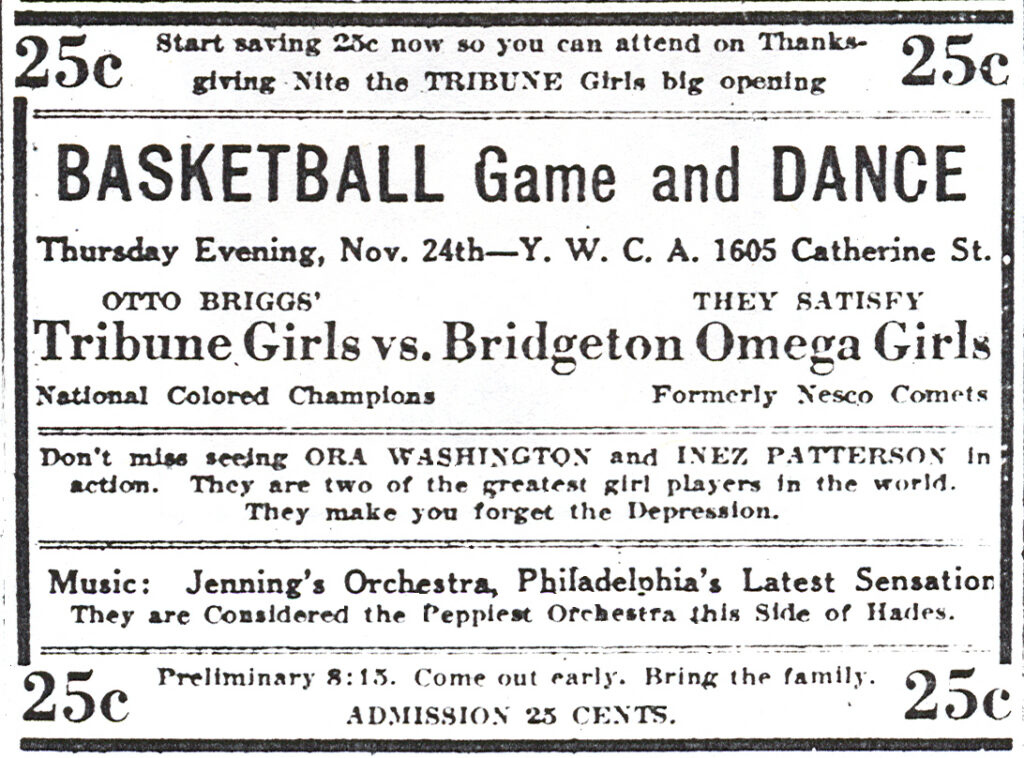

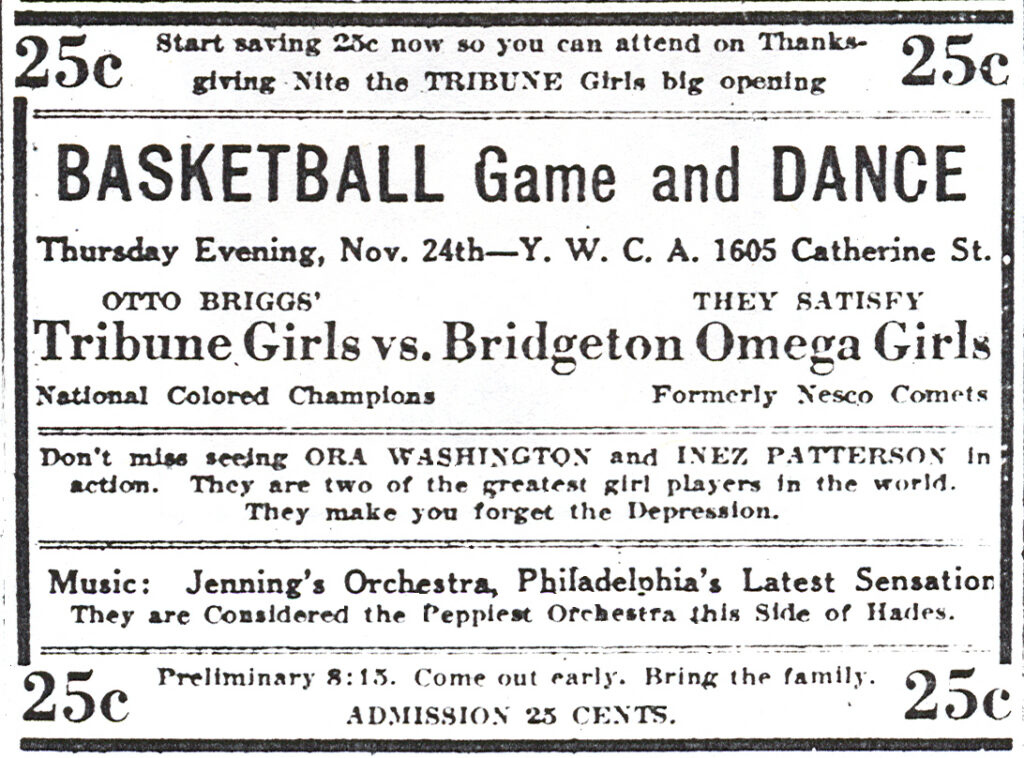

February 11: Ora Washington and the Philadelphia Tribunes

A tennis and basketball phenomenon, Ora Washington became Black America’s first female athletic star in the 1920s and 1930s. She made her basketball reputation as the leader of the Philadelphia Tribunes, sponsored by Philadelphia’s Black newspaper.

As one admirer put it: “No one who ever saw her play could forget her, nor could anyone who met her.”

Images courtesy of the Philadelphia Tribune.

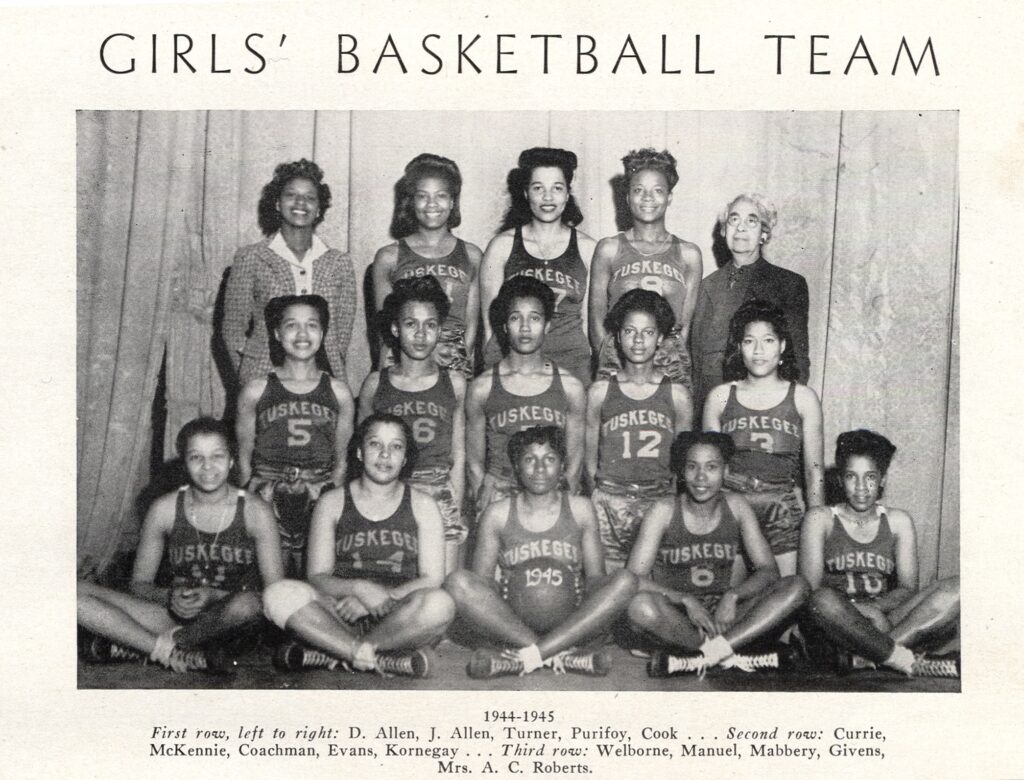

February 13: Alice Coachman

Tuskegee University had an especially strong women’s basketball team. In 1929, visionary athletic director Cleveland Abbott began to recruit young women for the school’s renowned track team. Speed and strength transferred smoothly to basketball. Alice Coachman won the high jump gold medal in the 1948 Olympics, becoming the first woman of African descent to win an Olympic medal. She also loved basketball.

“I was what you may call the rebounder,” she explained. “Every time the ball would go to the backboard it was mine. To get that ball off that backboard, knowing that nobody else could jump that high. That was thrilling. I was just as good in basketball as track. If things were as they are now, I probably would be at some university going with the Olympic team in basketball.”

Photo courtesy of the Tuskegee University Archives.

February 14: Margaret Sexton

From the 1920s into the 1960s, the winner of the Amateur Athletic Union national tournament was widely considered the best team in the nation, although such claims were limited by the lack of Black teams, which were rarely invited. Each spring, teams representing companies, business colleges, and a few four-year colleges competed fiercely for the title.

“It meant an awful lot to me,” explained 5-time AAU champion Margaret Sexton. We gave up meals—I mean you didn’t have time to eat. A lot of times after work you just ride the bus and go to practice or whatever and it was really wonderful.”

Photo courtesy of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

February 15: Hanes Hosiery

The Hanes Hosiery Girls, who worked and played for Hanes Hosiery in Winston Salem, N.C., won the AAU championship in 1951, 1952, and 1953.

Eckie Jordan (front), who stood 5’2″, was a mainstay of the team and was named AAU tournament MVP in 1951. “Coach thought I was too short to play,” she noted, “but I proved him wrong.”

Photo courtesy of Eckie Jordan.

February 16: Beauty Queens

The AAU women’s basketball tournament, which crowned the nation’s top team, often featured a beauty contest. Jimmie Vaughn (in crown) added the title of queen to accomplishments that included All-American honors, a free throw championship, and multiple national titles. Cornelia Lineberry (in knee pads) was named queen in 1947.

Photos courtesy of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

February 17: Nera White

With an AAU career that lasted from the mid-1950s through the 1960s, Nera White was acknowledged as the best female player ever, named an All-American an unprecedented 15 times.

“They think some man came up with the first finger-roll layup. Not true. Nera White did that forever.” – Margie Hunt, Wayland Baptist player

Photo courtesy of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

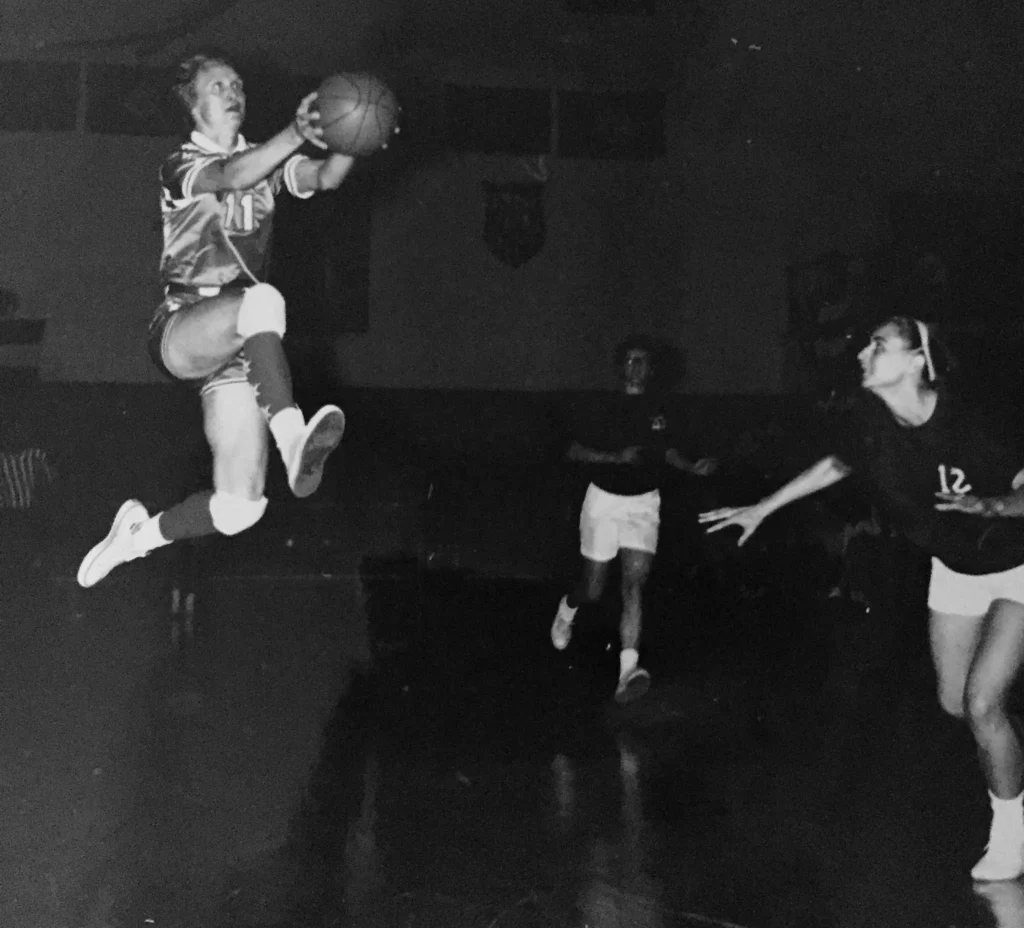

February 18: Wayland Flying Queens

The Wayland Flying Queens from Wayland Baptist College dominated AAU play for most of the 1950s, winning six of eight titles between 1954 and 1961. They were named for their mode of transportation – local enthusiast Claude Hutcherson flew the Queens to games in his fleet of Beechcraft Bonanzas.

It was unusual for a college to sponsor a top-flight women’s team, and players leaped eagerly at the chance to go to college while playing the sport they loved.

Carla Lowry, who grew up in small-town Mississippi, would never forget the moment she picked up a copy of Parade magazine and saw the Queens on the cover. “It said that they had won their eighty-first game and their third national championship. I thought: ‘By God, I want to go play with those guys.’ So I hopped on a bus.”

Photo courtesy of Wayland Baptist University.

February 19: Highland High Ramlettes

In the spring of 1949, North Carolina’s Highland High Ramlettes traveled from Gastonia to Durham to play in the all-Black NCAC women’s basketball tournament. They took the crown.

The trip was almost as exciting as the victory. As tournament MVP Gladys Thompson (#36) pointed out:

“Girls didn’t get to go many places. I had a strict mom. She was strict. And to get to go to Durham, North Carolina. That was a long way for us. Girls now they have boyfriends that just drive. But see they didn’t have cars to take us places then. As a matter of fact, when I played basketball, I wasn’t courting. My mama didn’t allow me to court until I graduated from high school. She did not. You had a friend to take you to the prom, but that’s it.”

When Gladys Thompson was eventually allowed to court, she married classmate Ervin Worthy and had a son named James. Since Ervin Worthy never played the game, any talent NBA great James Worthy inherited came from his mother.

Photo courtesy of Highland High School Alumni Association.

February 20: Nashville Business College

In the 1960s, Nashville Business College became the most successful team in AAU history, winning 10 of the 12 championships held between 1958 and 1969. Coach John Head put together a stellar group of players that included superstar Nera White and future coaching great Sue Gunter.

Head’s approach was simple; the team ran two defenses, two offenses and two breaks. Players practiced them every day, and that was all they needed. As Gunter put it: “Everybody that we played knew exactly what we were going to do when we came into the gym. It wasn’t a matter of scouting us. But they couldn’t beat it, because of the execution.”

NBC championship team, 1960. John Head is at center, Sue Gunter just to the left and Nera White at far left. Photo courtesy of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

February 21: American Institute of Business

In honor of my arrival in Iowa, longtime hotbed of women’s basketball, here is the team from Des Moines’ American Institute of Business, one of many AAU teams sponsored by “business colleges” that primarily taught secretarial skills. AIB was runner-up in the 1943 AAU tournament, losing to another Iowa school, Davenport’s American Institute of Commerce.

Photo reproduced, with permission, from the Collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Library.

February 22: Iowa Women’s Archives

So wonderful to finally visit the Iowa Women’s Archives, where women’s history – including women’s basketball history – is preserved and protected. Its permanent endowment was financed by co-founder Louise Noun, who raised the funds by selling her Frida Kahlo painting, Self-Portrait with Loose Hair.

Strong-Minded Women Make History!

Photo reproduced, with permission, from the Collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Library.

February 23: Missouri Arledge Morris

In 1955, Missouri Arledge became female basketball’s first Black All-American. The Supreme Court had just issued its Brown decision, and institutions across the country felt pressured to desegregate. Arledge’s college team, Philander Smith, was invited to the AAU tournament. They reached the quarter finals, upsetting the number four seed along the way. Arledge’s play won her the All-American honor.

Arledge, who stood just over 5’10”, did not start to play until eighth grade, when Carl Easterling, the girls’ basketball coach at Hillside High in Durham, N.C., spotted her in gym class. At first she only went to practice because Easterling provided a personal escort. “He would come to my class, the last class of the day and wait outside the door, take me by my hand and walk me up to the gym,” she explained. “That’s the only way I would stay.” Finally, Easterling tired of the daily walk and tried a bribe. “If I did well, he would try to ensure that I got a scholarship to college.” Many black colleges still fielded women’s teams, and her talent earned her a dozen offers. She picked Philander Smith.

As happened so often with desegregation efforts, however, early progress quickly lagged. The next Black All-American, Sally Smith, would not be named until 1969.

Photo courtesy of the Morris family.

February 24: Work and play

Life on a company team was far from glamorous. At Hanes Hosiery, for example, players worked full-time jobs, and team responsibilities included taking care of their own uniforms.

Basketball skill did not necessarily transfer to factory work. While Eckie Jordan felt at home on the court, she was lost on the production line. “I started working in the seaming department but I didn’t stay on that seaming job any time,” she explained. “That’s when you still had seams, and I never did sew a straight one and so a year later I was in the office.”

Photos courtesy of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

February 25: Rapid City Indian School Tournament

Although Shattering the Glass covers many key moments in women’s basketball history, there’s always more to learn.

We’d love to know more about this picture of a tournament held for teams from Native American schools, which we found in the National Archives. How did these young women weave basketball into their challenging lives?

(Addendum: a friend responded to our call with a fascinating article: https://www.sdhspress.com/…/we-are…/4102_davies.pdf)

Photo courtesy of the National Archives–Central Plains Region, Kansas City, Missouri.

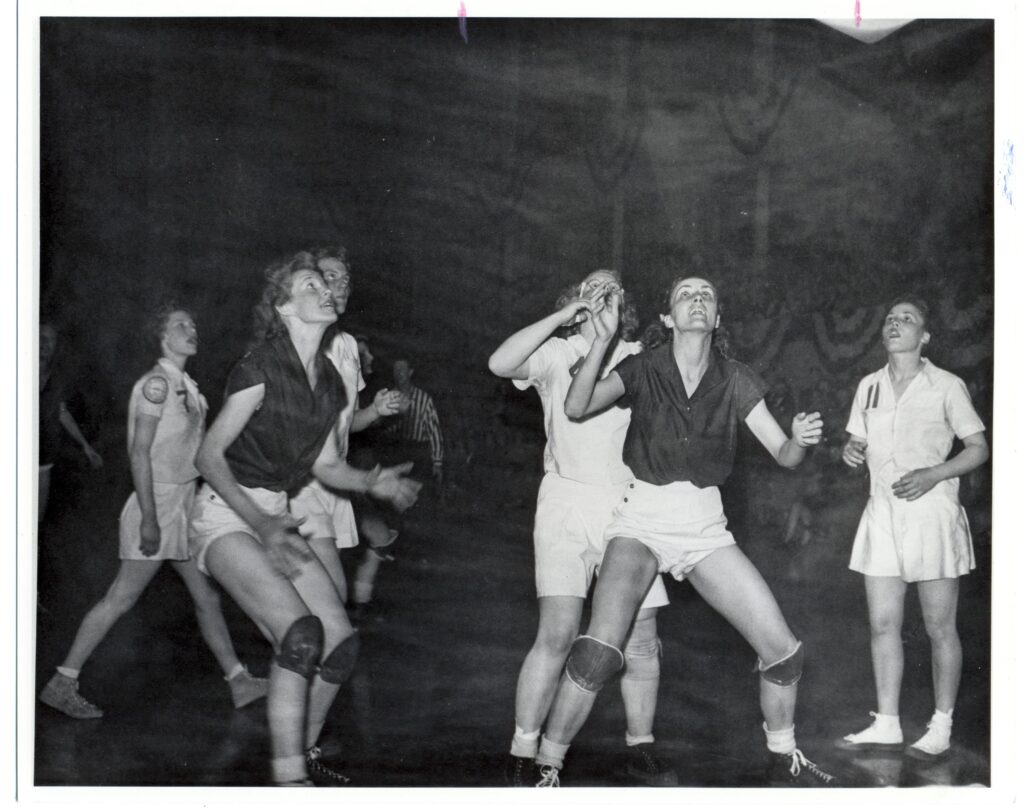

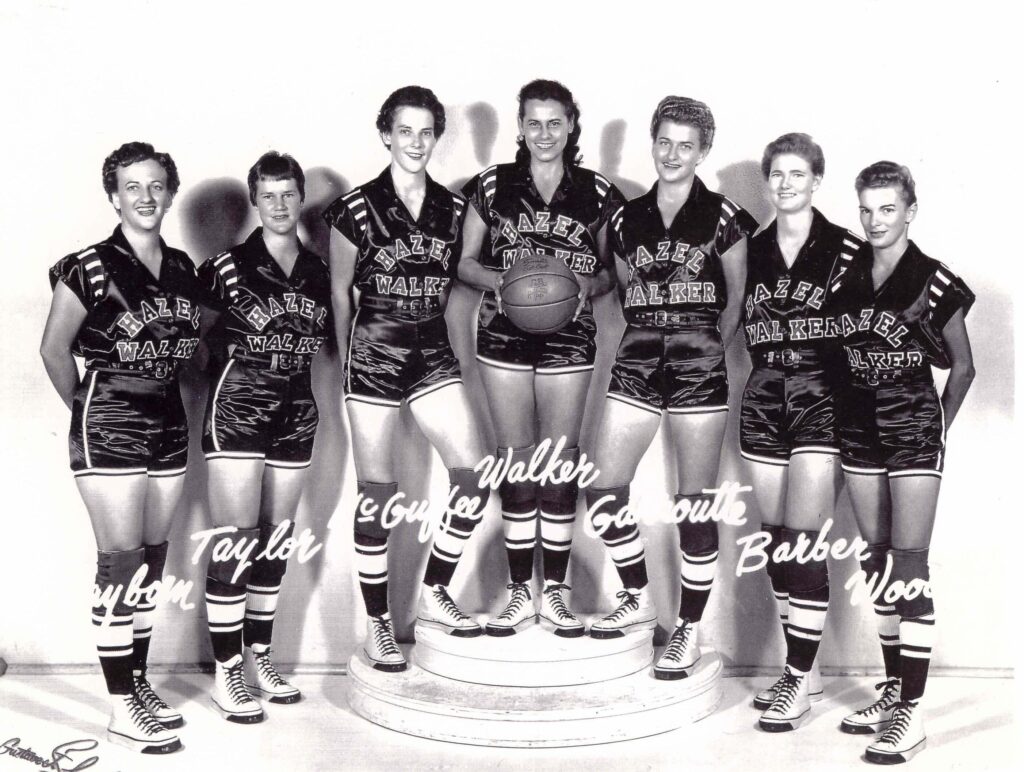

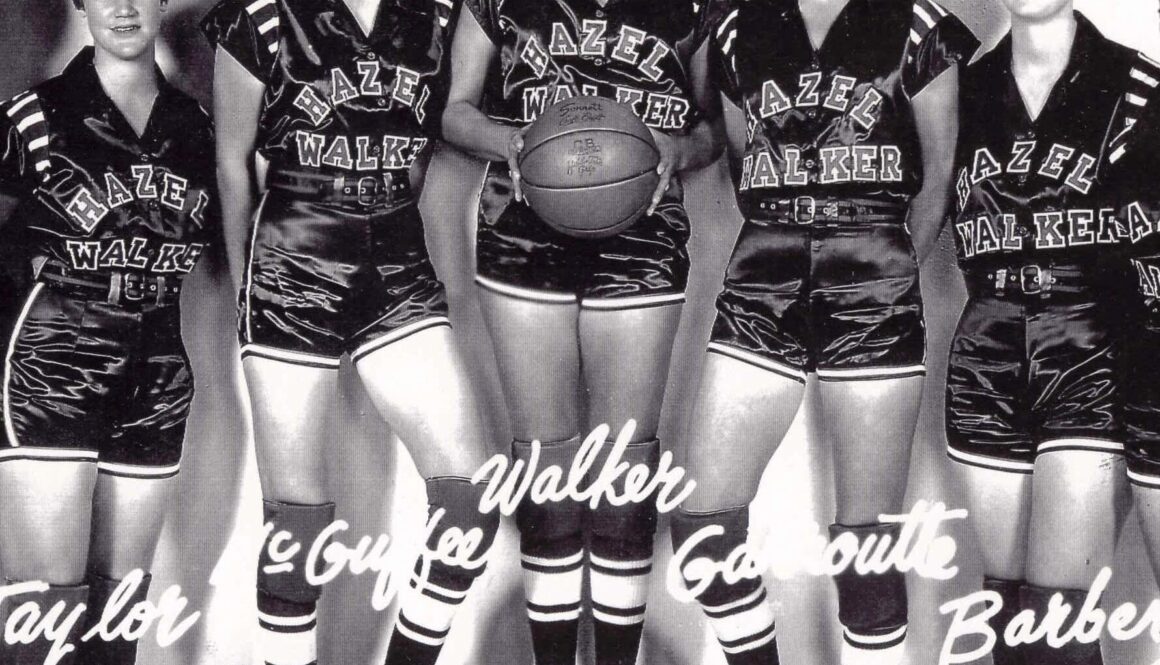

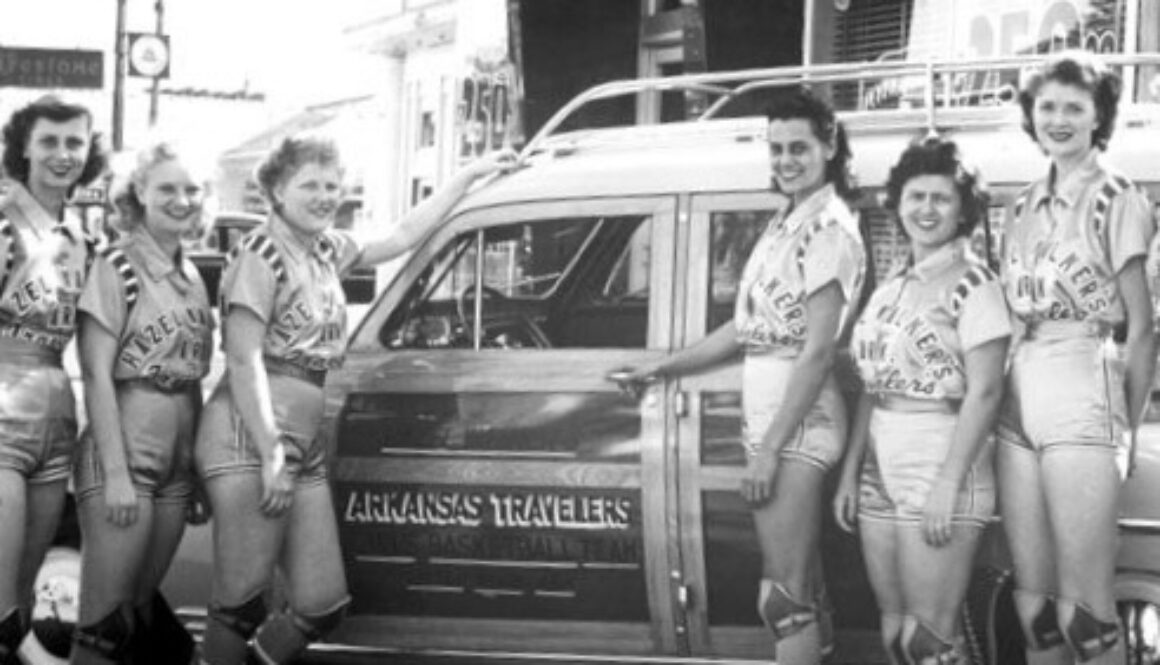

February 26: Hazel Walker’s Arkansas Travelers

From 1949 to 1965 a women’s basketball team traveled the Midwest and South, taking on men’s teams in town after town and usually beating them. Hazel Walker’s Arkansas Travelers was spearheaded by Hazel Walker, an Arkansas native who had been one of the AAU’s brightest stars before she decided to take the leap to the professional ranks.

The Travelers followed a grueling schedule. “We had a lot of doubleheaders,” Walker noted. “Sometimes we would play one game at seven and then drive forty miles and play again that same night. Then we had to get up and move the next day. We played eleven or twelve games a week sometimes.”

But for women who loved basketball, it was ideal. “Once you make up your mind, that is all there is to it,” Walker wrote Francies “Goose” Garroutte in a recruiting letter. “I guarantee you, you will be happy, satisfied, have the best time you ever had or will ever have, save money, and play all the basketball you want to.”

Photo courtesy of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

February 27: Cheerleaders

The conservatism of the 1950s hit hard at women’s basketball, and many schools eliminated women’s teams. Although C. Vivian Stringer (left) was one of the best pickup basketball players in her hometown of Edenborn, Pennsylvania, the closest she could get to her high school court was as a member of the cheering squad.

“My satisfaction was that on Saturday or Sunday the boys would still come down and play,” she recalled. “Sometimes these guys would walk maybe a couple of miles just to come over to the Edenborn basketball court.”

Photo courtesy of the German-Masontown Public Library, Masontown, Pennsylvania.

March 1: Title IX

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

On this first day of Women’s History Month, thanks to Rep. Patsy Mink, Rep Martha Griffiths, and the many other dedicated advocates who brought us Title IX.

Rep. Patsy Mink, left, Rep. Martha Griffin, right. Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress.

March 10: Fighting for Resources

Before Title IX, players and coaches lucky enough to have college teams had to scramble for resources. Kay Yow, Sue Gunter, Chris Weller and other early coaches fought constant battles over basics such as uniforms and locker room space.

When C. Vivian Stringer got her first coaching job at historically Black Cheyney State College, she spent her own money to recruit and drove her team to games in an old, highly unreliable prison bus. Intersections were a challenge, she recalled: “I’d slow down but not enough to stop because we weren’t sure we were going to start again, so my assistant would crane her neck out the window and yell, ‘Vivian, keep going, no one’s coming.’”

As longtime University of Texas coach Jody Conradt pointed out: “Back then, the only reason to be a female college athlete was that you loved it.”

Sue Gunter, left, courtesy of East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University; C. Vivian Stringer, right, courtesy of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

March 11: Making Law Reality

In the early 1970s, the Stanford women’s basketball team was fed up with second-class treatment – no locker room, no official uniforms, a tiny gym with no room for spectators. With the determination inspired by the women’s liberation movement, they let athletic director Dick DiBiaso know.

“We just showed up without an appointment, sat in the lobby until he agreed to see us, then listed our complaints, demands and requests,” team member Mariah Burton Nelson (#12) explained. “We told him Title IX had passed and that it was his job to start implementing it. We were angry. We were persistent. We were, I’m sure, a pain in the neck.”

As elsewhere in American life, the passage of landmark federal legislation was only a beginning. It had to be enforced – often against significant opposition. Women who sought to turn Title IX into reality had to take matters into their own hands.

Stanford University basketball team, 1975. Courtesy of the Stanford University archives.

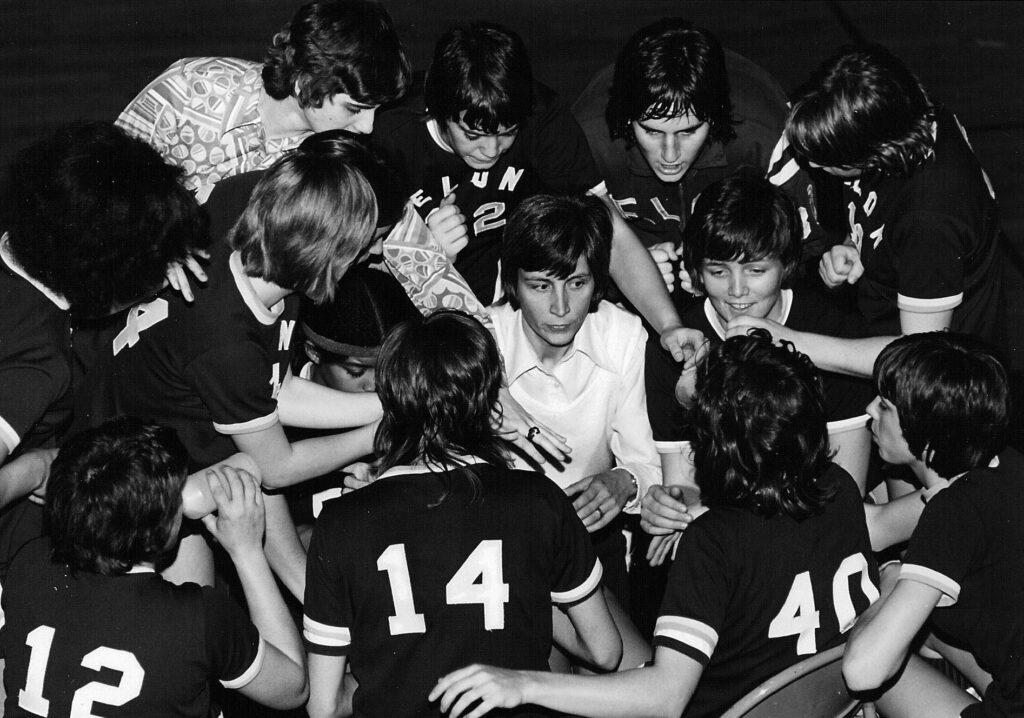

March 12: The First National College Championship

In its early years, women’s college basketball was run by the Association of Intercollegiate Athletes for Women (AIAW). Formed by physical educators, the organization played a major role in ensuring that Title IX was applied to sports.

AIAW members believed in women’s strength and independence. “These women were so strong,” recalled C. Vivian Stringer. “They had doctorate degrees and stood up for their rights. My role models were women for once in my life.”

Early leaders were leery of the academic and recruiting scandals that plagued the male athletic model. They banned athletic scholarships and limited recruiting. Still, they began to build frameworks for competition.

The first national college tournament was an invitational put together by coach Carol Eckman at West Chester State College, near Philadelphia. In 1969, the West Chester team, starring future coach Marian Washington, won the first title. Eckman would hold two more invitational championships before the AIAW organized its first national tournament in 1972.

West Chester championship team, 1968-69, with Carol Eckman (back row, center) and Marian Washington (back row, right). Courtesy of Special Collections, West Chester University.

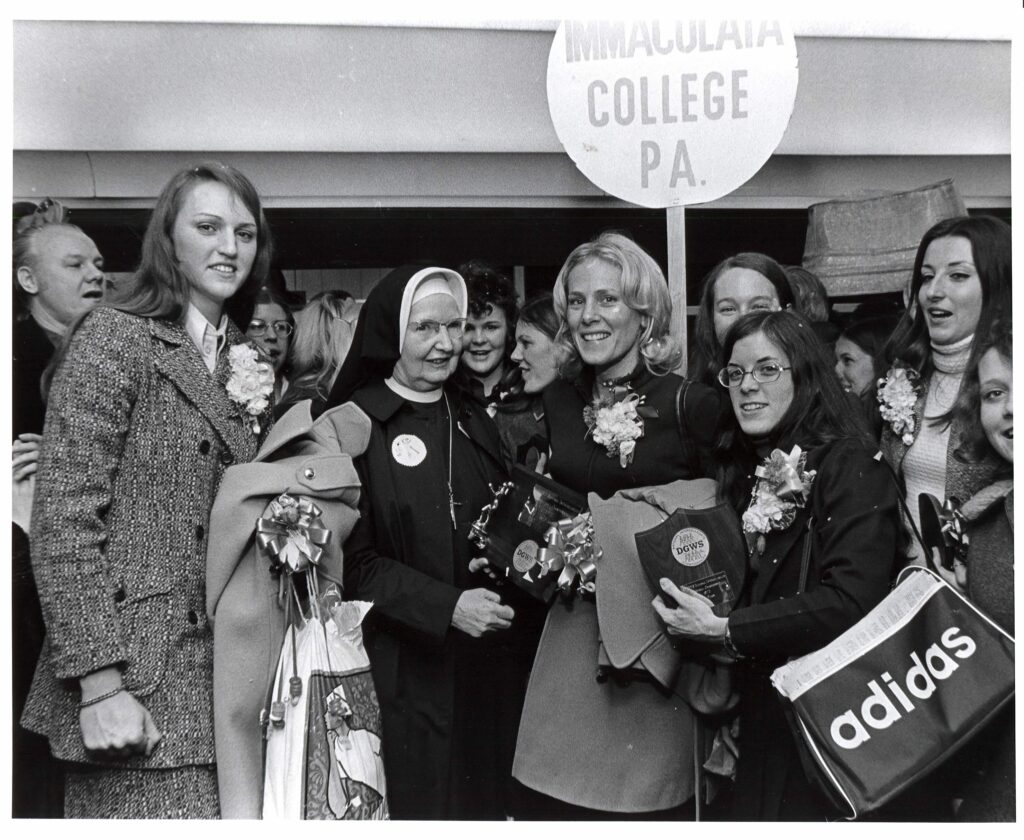

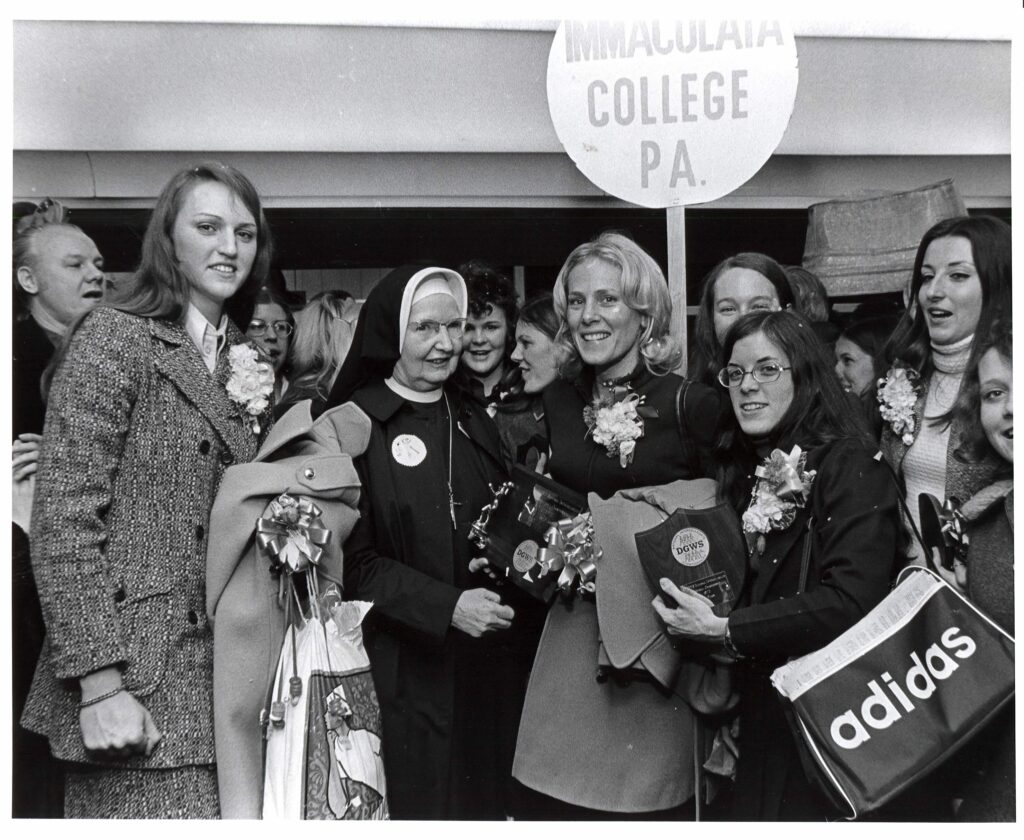

March 18: The Mighty Macs’ Three-Peat

The Mighty Macs from Immaculata College won the first three national tournaments held by the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW), a woman-led association that oversaw women’s college sports from 1972 into the 1980s.

Women’s basketball thrived in Philadelphia, with the Catholic church an especially prominent supporter. Young woman competed avidly in the city’s many pickup games, and in Catholic Youth Organization Leagues.

In 1972, on the strength of local players that included Marianne Crawford, Theresa Shank and Rene Muth, Immaculata defeated West Chester State, 52-48, to take the first AIAW title. They capped off an unbeaten season by winning the 1973 title, and completed their three-peat in 1974.

Crawford, Shank and Muth would all go on to become distinguished college coaches – Crawford’s Old Dominion teams won national championships in 1979, 1980 and 1985, and Shank led Rutgers to the AIAW title in 1982.

Immaculata team, 1972, including Theresa Shank (left) and coach Cathy Rush (center, blonde). Courtesy of Immaculata University.

March 20: Chris Weller and the Early Years of Title IX

As we sit at the Charlotte airport, heading to our signing in DC, we’re reminded of the pioneering work done by Hall of Fame coach Chris Weller at nearby Maryland.

Growing up in the 1960s, Weller was frustrated by the lack of athletic opportunities in her community. “They had nothing for girls sportswise,” she explained in an interview. “There were basically three career choices for women – secretary, teacher or nurse.”

As a student at the University, Weller helped to start a club basketball team, and as she played and organized team events, “I felt like I grew and found myself.” She became an outspoken advocate of opportunities for women.

When she became the women’s basketball coach in 1975, she worked to expand her team’s resources, and to convert the men’s coach, the legendary Lefty Driesell, to the cause, with some success.

“Finally, he understood I was just as passionate about my team as he was about his,” she said. “At press conferences where he went first, he would end by introducing me and saying, ‘Now those girls are serious.’ I cringed every time he would say ‘girls,’ but he’d come a long way.”

One day, Weller’s team was stood up by a group of male players they were supposed to scrimmage in preparation for a big game against Old Dominion. Driesell stepped in, dragging his team managers with him. “‘I’ll do what you need,’” she recalled him saying. “I told him I needed a tall player on the low block,” she continued, “and he said, ‘I can do that.’ To this day I regret not having a tape of Lefty running up and down the court with his managers playing us.”

Chris Weller, University of Maryland, 1978. Courtesy of Chris Weller.

March 22: Delta State Dominates

From 1975 to 1977, Delta State University, located in the small town of Cleveland, Mississippi, dominated the women’s college game. The Lady Statesmen upset three-time champion Immaculata in the 1975 championship, 90-81. They then took the next two titles.

The team had a deep history. Coach Margaret Wade (below, center) had been a member of the Delta State varsity back in 1933, the year that school administrators decided basketball was “too strenuous for young ladies” and abolished the team. “We cried and burned our uniforms,” Wade said, “but there was nothing else we could do.” Wade made a career as a high school coach. When the Delta State team re-formed in the wake of Title IX, she became its coach.

The Lady Statesmen also embodied the sport’s future. In 1974, Mississippi’s top high school player in the state was Lusia Harris (below, second from right) in nearby Greenwood. Although Delta State was a historically white school, and Harris was Black, recruiter Melvin Hemphill drove over to Greenwood to talk to her.

Harris had planned to attend historically Black Alcorn State, but that school had no women’s basketball team. She agreed to take the leap. Brushing off racist comments from opposing teams’ fans, she played a key role in the team’s successes. She then became a central player in the first U.S. Olympic team, which won the silver medal in the 1976 Olympics. In 2022, just before she passed away, the New York Times produced an Oscar-winning short documentary on her life.

Delta State team including coach Margaret Wade (center) and Lusia Harris (second from right). Courtesy of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

March 26: The Women of Troy

As we and so many others wish Juju Watkins a smooth recovery from her ACL tear, we thought we’d spotlight USC’s first championship era, when the Women of Troy won back-to-back titles in 1983 and 1984.

Cynthia Cooper, Pam McGee (below, left), twin Paula McGee (below, center), and especially the charismatic, extraordinarily talented Cheryl Miller (below, right) represented a new trend in the women’s college game – an influx of skilled Black players from urban areas.

The Women of Troy played a fast, exciting brand of basketball. “We just ran,” recalled Paula McGee. “We were open court, and you had big players that could get down the floor. So we would play defense, rebound and run. We beat people because we ran the whole floor.”

USC was also the first championship team from a major media market. The work of USC’s well-heeled publicity department helped elevate the players from basketball stars to media personalities – female counterparts to the “Showtime” Los Angeles Lakers. The attention brought welcome new publicity to the women’s game.

In just two years, Juju Watkins has more than upheld that tradition with her dynamic performance and the attention she has brought to present-day women’s play. We send our best wishes to her and her team in this tough time.

Pam McGee (left), Paula McGee (center) and Cheryl Miller (right). Courtesy of USC Sports Information.

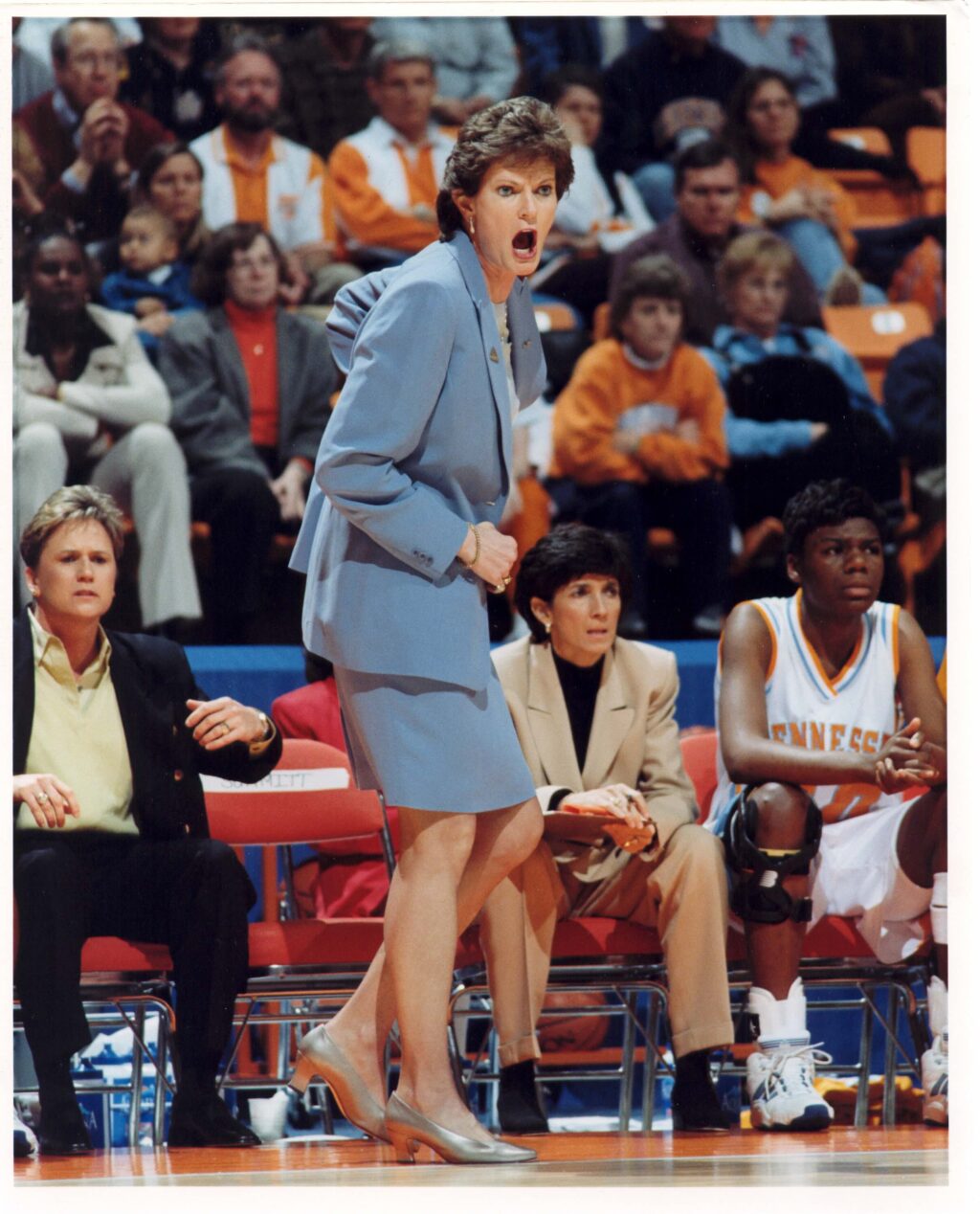

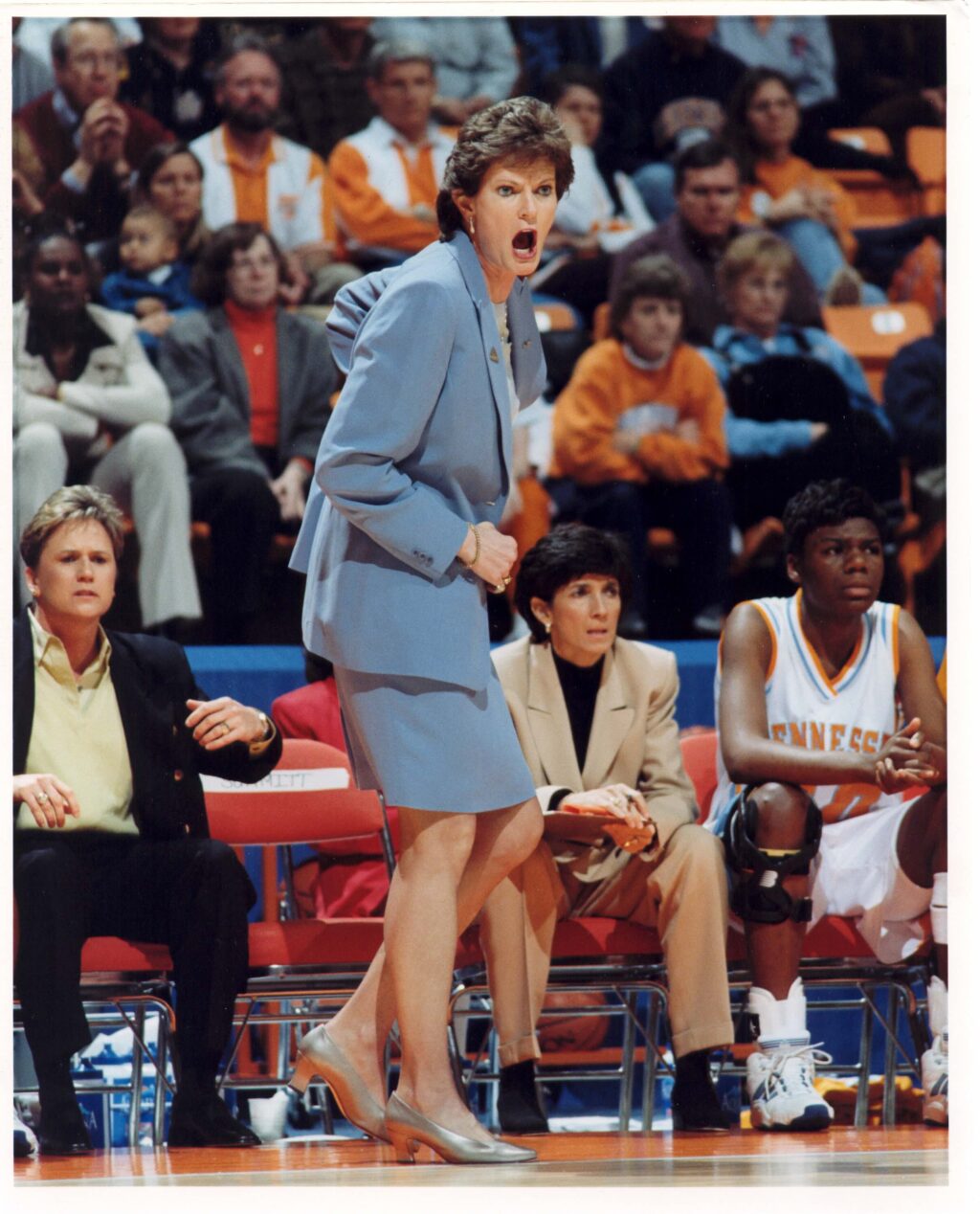

March 28: Pat Summitt

Here at the Birmingham Regional we ran into some reporters from the University of Tennessee, and of course we talked about the great Pat Summitt. Twenty years ago, when we wrote the first edition of Shattering the Glass, Pat was at the peak of her career, working toward what would be eight national titles. We loved watching her coach and we miss her greatly, as does the game she helped build.

She was so much larger than life. In the first edition, we noted that she had “filled state lore with legendary stories. There was her hardscrabble childhood on a family tobacco farm, ruled over by a stern father who was far quicker with his belt than with a compliment. There was her gutsy, self-driven rehabilitation of her torn knee ligament, often considered a career-ending injury in those days. There was her decision to undertake a key recruiting trip while nine months pregnant, and the hurried flight back to Knoxville when she went into labor. There was The Stare—a penetrating gaze that related more than words. In Tennessee, she drove as fast as she wanted and never got a ticket. Her standard entrance into spacious Thompson-Boling Arena resembled that of a rock star—a solo stroll to waves of thunderous applause.”

One of the toughest parts of writing the second edition was chronicling Summitt’s death from early-onset Alzheimer’s at the age of 64. But at the same time, it was clear her influence would last far longer.

“She changed the history of the sport she loved—and of sports in general,” retired quarterback Peyton Manning observed at her “Celebration of Life.”

“Pat essentially transformed the model for women in this country from ornamental to active,” noted writer and friend Sally Jenkins. “She taught every young woman who came within 10 feet of her that you don’t let anyone define you. You became a strong, individual, independent young woman.”

Courtesy of Tennessee Athletics.

March 28: Jody Conradt

On Saturday, just after the Texas Longhorns defeated the Tennessee Lady Vols in a close, dramatic Sweet Sixteen game, my co-author Susan looked up from the sink in the media bathroom and realized that she was standing next to legendary Texas coach Jody Conradt.

Conradt, who had come to Birmingham to support the Longhorns, coached the team from 1976 to 2007. In 1986, she led them to an undefeated season and the national championship.

As we wrote in Shattering the Glass, Conradt was a calm woman who coached in a deliberate, undramatic style. She was not cut out for media stardom. But Texas citizens, schooled in the hard lessons of a frontier past, valued achievement and state pride over appearance or convention. Conradt fit that mold to perfection, with grand ambitions and the drive to realize them. “If you grow up in Texas, you develop a sense of pride early on about this state,” she explained. “That pride builds confidence, a can-do attitude.”

Working with women’s athletic director Donna Lopiano, a power in her own right, Conradt shaped teams that embodied a straightforward mix of strength and excellence. In the process, she built a loyal audience that featured some of the Lone Star State’s most powerful female leaders, including U.S. congresswoman Barbara Jordan and future governor Ann Richards.

“Those women didn’t start coming because they liked basketball,” she noted. “They came because they identified with the perception that women athletes are strong women. They saw the UT women’s basketball team excelling where women hadn’t excelled before.”

Jody Conradt, left, with Clarissa Davis, MVP of the 1986 championship. Courtesy of University of Texas Athletics.

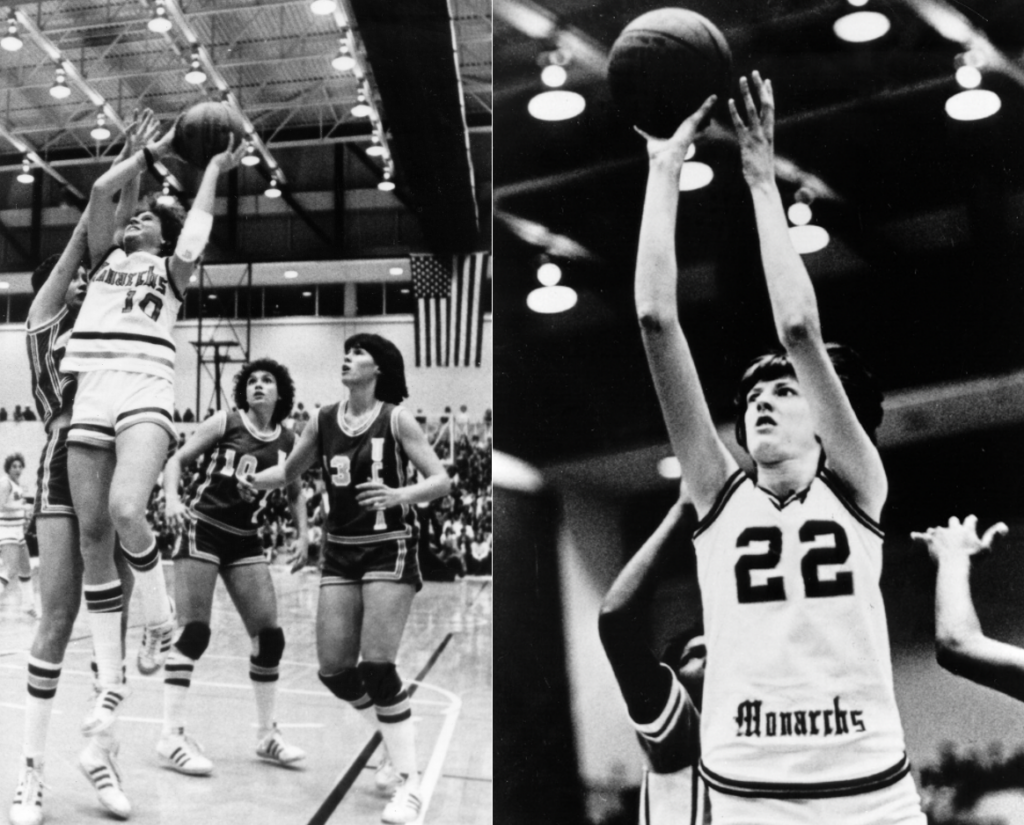

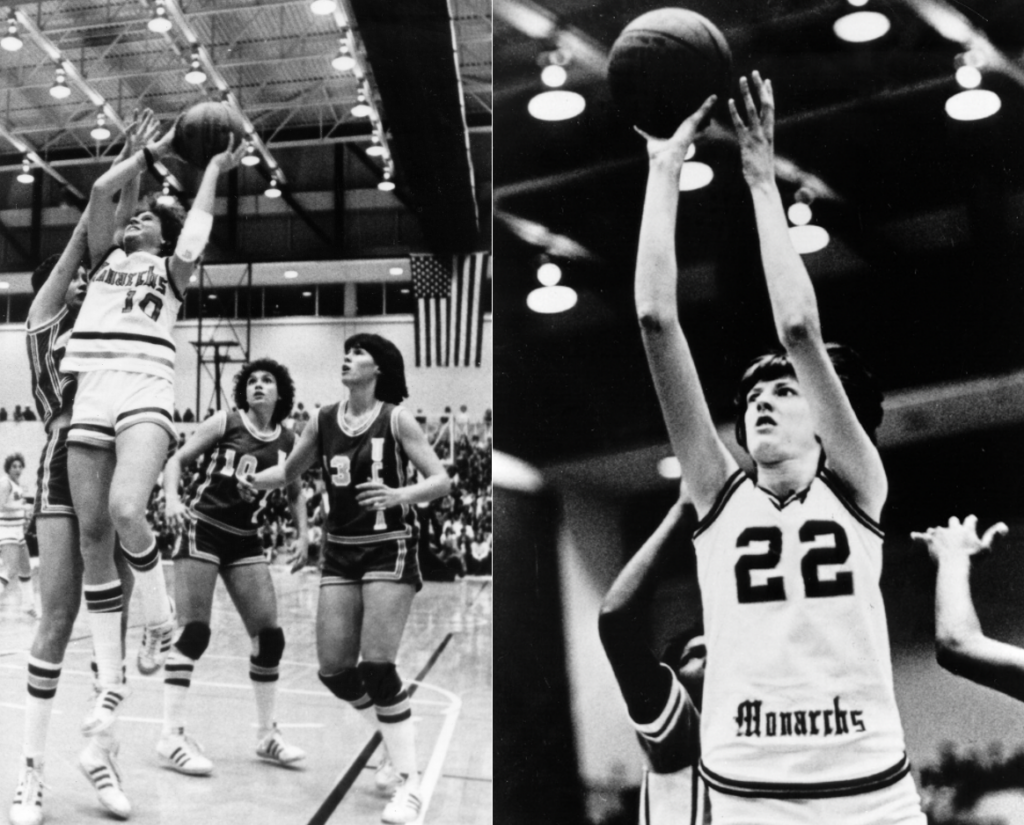

April 1: Lady Monarchs

The Final Four is set, and four storied programs will compete for this year’s title.

South Carolina and UConn have both won multiple national championships. Texas took the crown in 1986. In 1974, UCLA awarded its first full women’s athletic scholarship to superstar Ann Meyers, and won the 1978 AIAW title.

As we anticipate the coming contests, we’re revisiting some past champions, starting with the Lady Monarchs of Old Dominion.

Old Dominion leaped to prominence in 1976 when the school signed Nancy Lieberman, the nation’s top recruit. Lieberman had honed her skills in New York’s high-octane playground matches, and her determination knew few bounds. She had skipped her high school graduation for the Olympic tryouts, made the team and taken home a silver medal.

The school also hired a new coach, Marianne Crawford Stanley, who had won three straight national titles with Immaculata College. Stanley and Lieberman clicked, and the team beat Louisiana Tech for the 1979 title.

On the heels of that victory, Stanley signed another top recruit – Anne Donovan – and defeated up-and-coming Tennessee to win a second straight title. Stanley would lead Old Dominion to a third title in 1985.

The Lady Monarchs routinely sold out the school’s 5,000-seat field house, and attendance occasionally topped 10,000 with standing-room-only crowds. “We were celebrities at Old Dominion,” Lieberman later recalled. “Nobody counts more in that town than a Lady Monarch.”

Nancy Lieberman, left, and Anne Donovan. Courtesy of Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia.

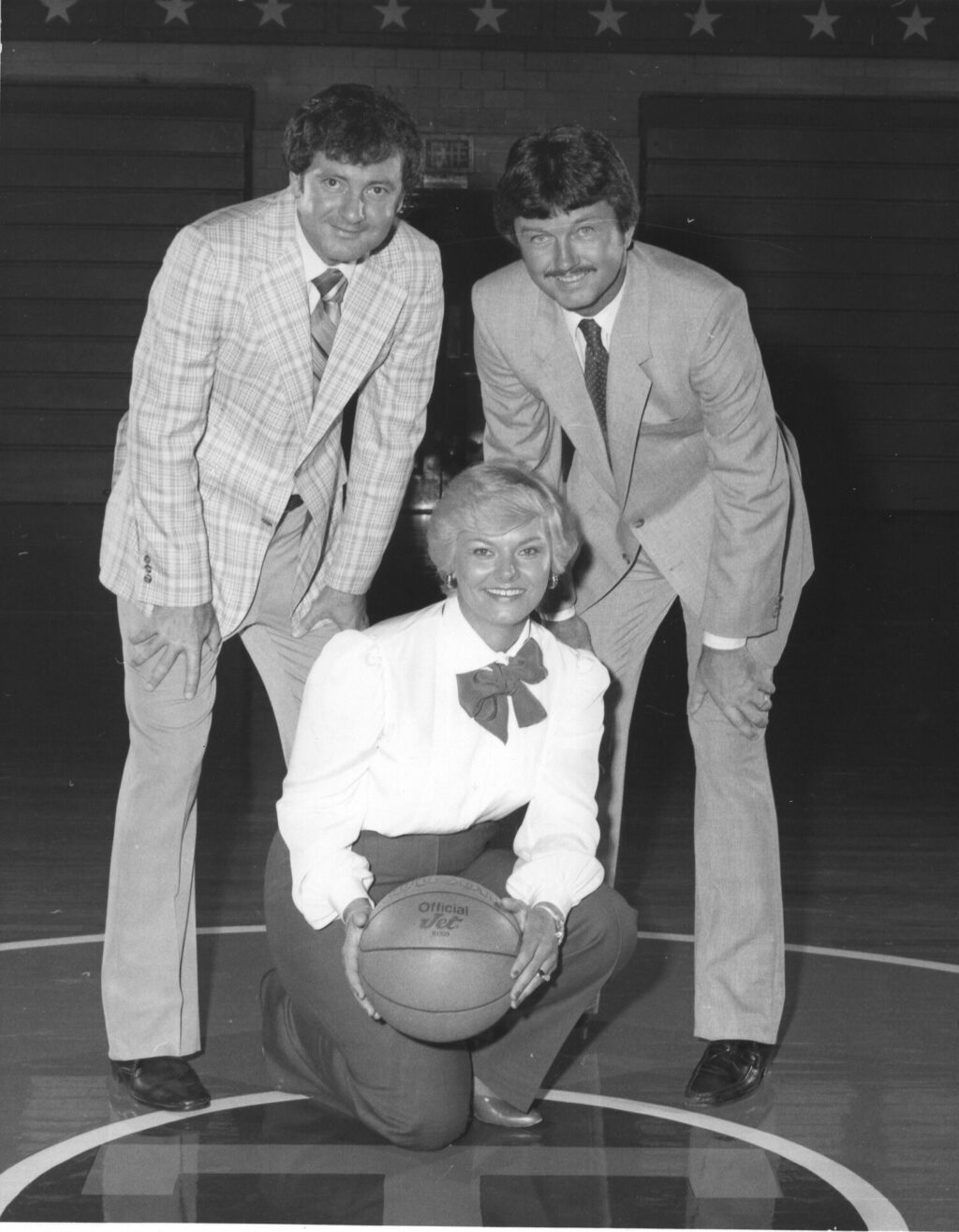

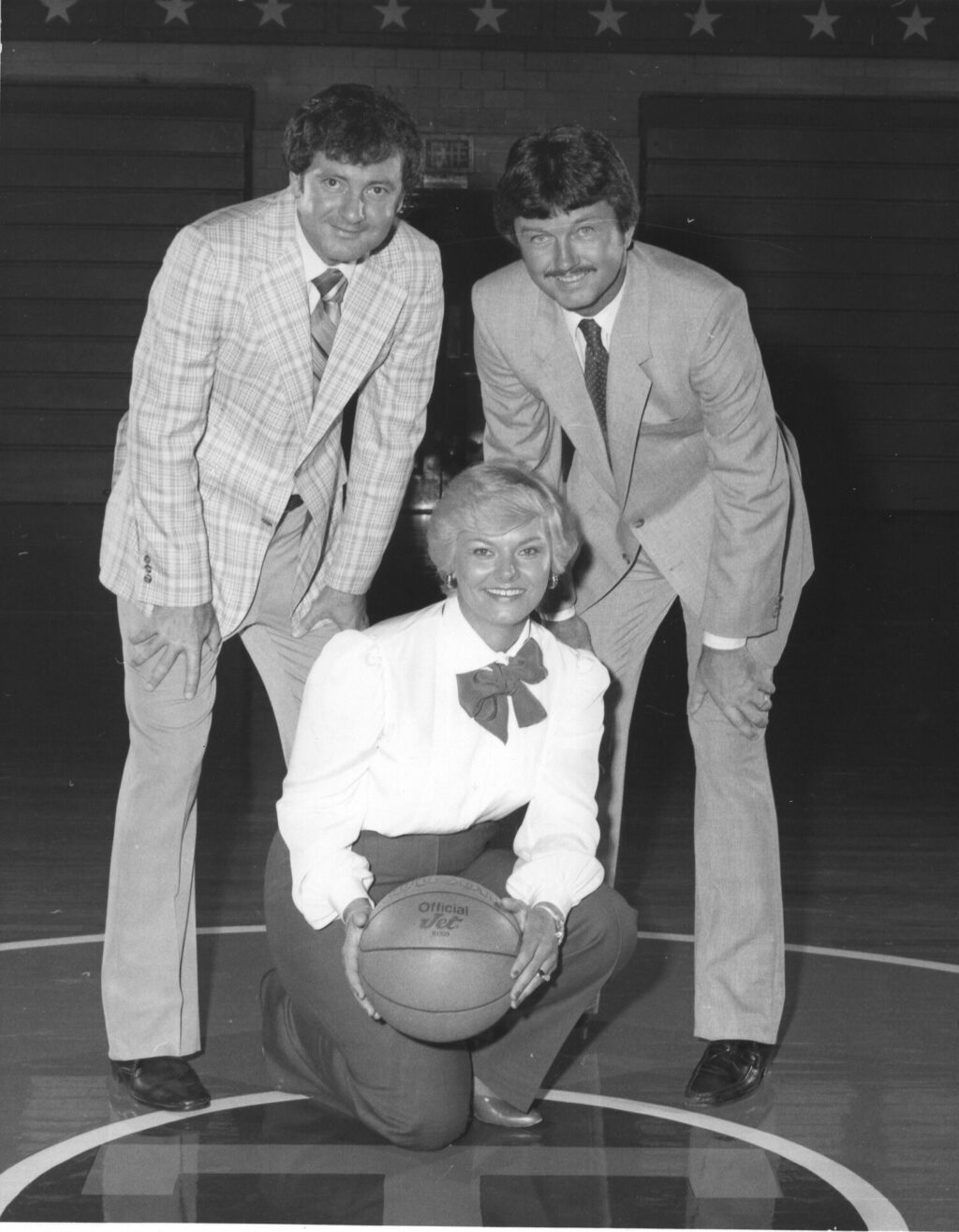

April 2: Lady Techsters

Next up in our list of champions: the Lady Techsters of Louisiana Tech, started in 1974 by legendary coach and personality Sonja Hogg.

Hogg, a La Tech graduate who had started as a physical education instructor, offered a formidable mix of competitive spirit tempered with southern charm. She became known for her flamboyant style, which often favored white outfits and spike heels. “I still remember when she came to recruit me,” recalled three-time All-American Pam Kelly. “She pulled up in a big white Cadillac and had on a bright white fur coat and with her white hair, you couldn’t miss her.”

Realizing her talents lay more in promotion than in on-court strategy, Hogg brought in assistant coaches Gary Blair (below, right) and Leon Barmore, who eventually became head coach. Recruiting almost exclusively from Louisiana and Mississippi, the coaches put together teams that won the AIAW national championship in 1980, the first NCAA tournament in 1981, and a third title in 1988.

Along the way, the Lady Techsters developed a fervent following, leading the nation in attendance from 1981 through 1984. Stars that included Pam Kelly, Angela Turner and Janice Lawrence became household names in north central Louisiana. Point guard Kim Mulkey would become a storied coach in her own right, leading teams to three national championships with Baylor and one with LSU.

Sonja Hogg, Leon Barmore (left) and Gary Davis. Courtesy of Louisiana Tech Athletic Media Relations, Ruston.

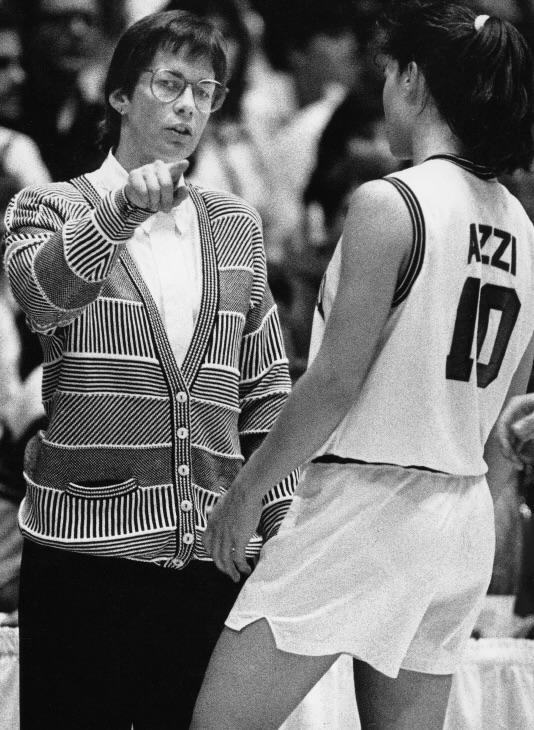

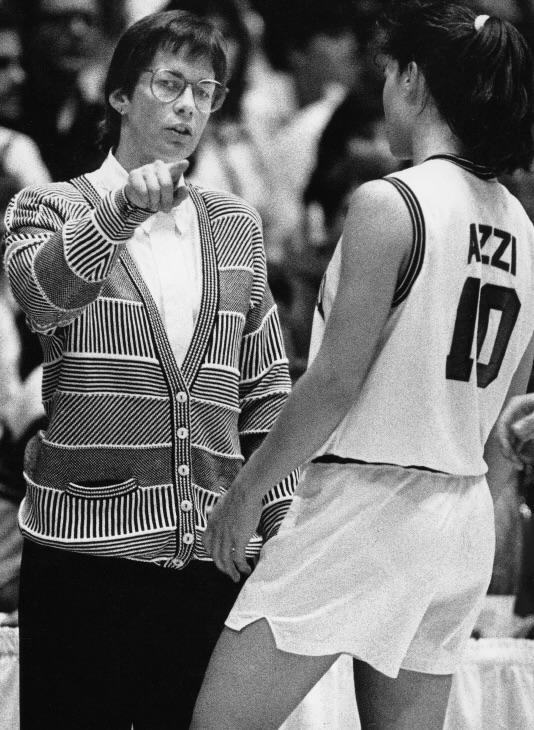

April 4: Tara VanDerveer

We’ve arrived in Tampa and are waiting for the Final Four to start. It seems a great time to revisit the career of coaching great Tara VanDerveer.

VanDerveer grew up in upstate New York, and pursued basketball with passion from an early age. When local boys left her out of playground pickup games, she saved up her allowance and bought the best basketball she could find. “If the boys wanted to use the ball, they had to take me with it,” she later wrote.

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, opportunities did not come easy. Her junior high school had no team, and her high school team “played all of four games but held no practices.” When she enrolled at the University of Indiana, which had one of the strongest women’s programs in the country, her team’s second-class status was palpable: “Basically, it was steak for the men, hot dogs for the women.”

Still, she persevered. In 38 years coaching at Stanford, she nurtured generations of young women, took her teams to three national championships, and retired with the most lifetime wins in college basketball history. She coached the high-profile 1996 Olympic team to a 60-0 record and the gold medal.

Along the way she became a tireless advocate for the sport, doing everything she could to demonstrate the heights of skill, teamwork and just plain excellence women could reach. “I’m always telling my Stanford players to put out their best effort every single game because somewhere out there someone is watching women’s basketball for the first time,” she wrote in an account of the Olympic year. “We want to give them a reason to tune in again.”

Tara VanDerveer with Stanford player Jennifer Azzi. Photo by Rod Searcy, courtesy of Stanford University.

April 5: Muffet McGraw

At the Final Four, in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame exhibit, one case held a set of accessories: a pair of green pumps, a bottle of bright green nail polish and two scarves – one green, one leopard.

Who could it be but Muffet McGraw, longtime coach of the Notre Dame Fighting Irish?

McGraw was one of the most thoughtful people we interviewed, discussing her own experiences as well as the challenges she sees ahead.

Over 33 years with the school, McGraw built her program into one of the most respected in the nation. She recruited outstanding players that included Ruth Riley, Jewell Lloyd, Skylar Diggins-Smith and Arike Ogunbowale. The team made seven appearances in the national championship game and won titles in 2001 and 2018.

Like many of her peers, McGraw focused on developing both skilled players and strong women. “Women struggle with confidence, smart talented women,” she told us. “I realized that’s my job. I have to build their confidence, so they go to the next level and use their voice.”

But she also learned from her players. She described the way that Skylar Diggins-Smith’s charismatic style, which initially clashed with the more methodical play she had traditionally encouraged, helped expand her understanding of the game. “Her whole demeanor was bigger than life and she showed it on the court,” she said. “My first thought was ‘Tone it down. We’re supposed be humble.’ Thank heavens I didn’t tell her. I later thought ‘Why should I?’ She changed me.”

She also highlighted the significance of the upcoming generation’s activism, most dramatically the viral video in which Sedona Prince exposed the vast inequalities between the men’s and women’s tournaments in 2021. Coaches from her era, she noted, tended to focus on their teams and overlook inequities; they were just so glad to have the opportunity to coach. “We continued that and kept passing it down,” she said. “This generation is speaking up, saying ‘We deserve more, we deserve to be treated equally.’”

Muffet McGraw cuts down the net at the ACC tournament, 2015. Courtesy of Fighting Irish Media.

April 6: Philadelphia

When we started Shattering the Glass, we didn’t realize we’d write so much about Philadelphia. But we did.

The city has nurtured generations of nationally recognized players, coaches and teams, including the remarkable Ora Washington, the country’s first Black female basketball star; the Mighty Macs of Immaculata College, who won the first three AIAW national championships; Notre Dame coach Muffet McGraw; Army West Point coach Dave Magarity and of course the two coaches in today’s championship game: Geno Auriemma and Dawn Staley.

Like so many Philadelphians, Auriemma and Staley grew up in working-class families and loved basketball from an early age. They carried that passion to the college level.

After working as an assistant for University of Virginia coach Debbie Ryan, Auriemma took over a struggling UConn team and propelled it to 11 NCAA championships, passing the extraordinary Pat Summitt of Tennessee, and compiling the most total victories in college basketball.

Staley pursued a stellar college career – also at UVA – played a key role in the 1996 Olympic Gold Medal team, and then joined the fledgling WNBA. She started coaching at Temple University while still playing professionally. She then traveled to Columbia, South Carolina, to take over a struggling South Carolina team, which she has so far led to three NCAA championships. Auriemma became one of the dominant coaches of his generation, she has become dominant in hers.

Both coaches have proved extraordinarily adept at recruiting, nurturing and retaining the nation’s most talented players, teaching them to fit into systems that emphasize team performance rather than individual stardom.

Longtime Auriemma colleague Phil Martelli once observed that if the coach’s admirers “think it’s an X’s and O’s thing they’re mistaken. It’s really about the way he handles people.” Rebecca Lobo concurred. “All of his players, while they are cursing him under their breath in practice, ultimately do anything he asks of them,” she said. “Not a lot of coaches develop that kind of loyalty. … He is very, very good at understanding each player he coaches, knowing whether a player needs to be yelled at constantly or prodded along gently. He knows how to read people … and what buttons he needs to push.”

Staley has become renowned for the way she convinces players who would be stars on any other team to forego immediate starting roles and instead come to see themselves as part of a team where every player contributes to success.

When she arrived in Columbia, Staley also focused on building a fan base that soon topped the nation in attendance. “One of the first things Dawn did was really get out into the community, letting them know more about the program and getting herself out there, getting her coaches out there,” noted longtime fan Nessie Harris. “And then when she started bringing those players in, the excitement, it just took off.”

Geno Auriemma, courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library, and Dawn Staley, courtesy of Barbara Lau.

April 7: A Defining Rivalry

UConn’s dominating victory in yesterday’s NCAA championship game – the twelfth in program history – once again placed the Huskies atop the women’s college basketball world. It also raised the welcome possibility of an ongoing, high-profile rivalry with the powerhouse Gamecocks of South Carolina.

Three decades ago, another UConn rivalry – this one with Tennessee – played a major role in drawing attention to the women’s college game.

Coached by Pat Summitt, the Tennessee Lady Vols drew the nation’s largest home audiences year after year. They won the NCAA title in 1987, 1989 and 1991. Then upstart UConn took the 1995 crown, and the rivalry was on. Summitt and Auriemma competed for recruits, honed their strategies, and prepared for annual showdowns that featured many of the nation’s top players, among them Rebecca Lobo (below, left) and Candace Parker (below, right).

Tennessee took the NCAA crown in 1996, 1997 and 1998. UConn surged back to win in 2000, 2002, 2003 and 2004. Tennessee reclaimed the title in 2007 and 2008. UConn replied in 2009 and 2010. The rivalry only ended when the tragedy of early-onset Alzheimer’s forced Summitt to stop coaching.

The two teams’ many strengths, combined with the coaches’ contrasting personalities, made for a colorful and heated rivalry. “Everyone who badmouths women’s basketball should be made to attend a Tennessee-UConn game,” a UConn beat reporter once observed. Summitt was the grande dame, carrying herself with a fierce dignity. Auriemma was the newcomer, a joking, needling troublemaker who once called Tennessee “the Evil Empire.” Their back-and-forth exchanges, which one sportswriter dubbed “The Pat and Geno Show,” heightened the drama.

The stakes were always high.

“Tennessee games were always the biggest matchups of the year,” UConn star Jennifer Rizzotti noted in 2001. “No matter how much we tried to downplay it, the team that won those games usually became number one in the country. It was a battle for bragging rights, and there was an intensity on the court that just wasn’t there with other opponents.” Interest in the contests soon stretched far beyond the two schools, as the games became regular features on national television and a spark for debates among sports fans around the country.

Rebecca Lobo, courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library, and Candace Parker, courtesy of Tennessee Athletics.

April 10: Kim Mulkey

Although Kim Mulkey’s LSU Tigers sat out the last two Final Fours, no one takes them for granted. Mulkey has compiled one of the most illustrious careers in women’s basketball. She won two NCAA titles while playing for Louisiana Tech. She then added four as a coach, three at Baylor and one at LSU. The LSU title came when Mulkey was spanking new with the Tigers. Opponents underestimate her at their peril.

The oldest of two daughters, Mulkey grew up in tiny Tickfaw, Louisiana. about 45 miles east of Baton Rouge. She learned basketball from TV and from her dad, who built a court in the family’s backyard. At Hammond High, she starred on four straight state championship teams, averaged 28.9 points a game and rolled up 4,075 career points. As a senior, she was the state’s Player of the Year, a Parade All-American and valedictorian of her class.

Fiery, focused and smart, she picked Louisiana Tech for college because of its fervent fan following, built by coaches Sonja Hogg and Leon Barmore. Standing 5’4″, she was a fast-moving maestro, blonde braids bobbing as she pushed the ball up the court. By the end of her senior year, she and her teammates had a 130-6 record, two national titles and one runner-up trophy. The first in her family to obtain a college degree, she won a NCAA post-graduate scholarship to study at LaTech and then spent 15 years as Leon Barmore’s assistant.

In 2000, she shocked the women’s basketball world by leaving her beloved Lady Techsters to become head coach at Baylor, taking on a team with only seven wins in the previous season. She set to work. The Baylor Bears took their first NCAA title in 2005, their second in 2012 and their third in 2019. The LSU title came in 2023. Mulkey became known not just for her coaching skills, but for her showy outfits and her sometimes-controversial statements, which brought her additional prominence.

“She is not only a great coach but she is an entertainer and she takes advantage of it to sell her team and her players and her program 24/7,” explained former college and pro coach Lyn Dunn. “Whether you love her or hate her, you’re going to tune in to see what she’s wearing. Let’s be honest. Our game is entertainment. I think we need more Kims.”

Kim Mulkey coaching at Baylor in 2010. Courtesy of Baylor University, Waco, Texas.