Recognition grows for Ora Washington

It is the summer of 2003 and I am sitting in the heart of Philadelphia, at a microfilm reader in the archives at Temple University. I squint at the dim screen as I crank through issues of the Philadelphia Tribune, tracking the five-game basketball series played by the Germantown Hornets and the Tribune’s Newsgirls back in 1932. I am having a fine time. The contest see-saws back and forth before my eyes, and the writing is a joy to read.

“The cash customers fanned to fever heat by the ardor and closeness of combat gave outlet to all kinds of riotous impulses,” Tribune sportswriter Randy Dixon wrote after Game 5 went into overtime, and the Newsgirls scored eight unanswered points to triumph 31-23. “They stood on chairs and hollered. Others hoisted members of the winning team upon their shoulders and paraded them around the hall. They jigged and danced, and readers believe me, they were justified. It was just that kind of a game.”

I have come to Temple in search of Ora Washington, the finest black female athlete of the early twentieth century. Basketball fans considered her “the greatest girl player of the age.” In tennis, the Chicago Defender once observed, her “superiority” was “so evident that competitors are frequently beaten before the first ball crosses the net.” Watching her play, one advertisement claimed, could “make you forget the Depression.”

I have come to Temple in search of Ora Washington, the finest black female athlete of the early twentieth century. Basketball fans considered her “the greatest girl player of the age.” In tennis, the Chicago Defender once observed, her “superiority” was “so evident that competitors are frequently beaten before the first ball crosses the net.” Watching her play, one advertisement claimed, could “make you forget the Depression.”

Then, however, she faded from view. In 1976, when she was inducted into a recently organized Black Athletes Hall of Fame, the Times reported that “the seat reserved for her on the dais the night of the induction ceremonies was empty. The silver bowl, gold ring and medallion she was to receive have been returned to the Hall of Fame offices in New York. And Miss Washington’s whereabouts remain a mystery.”

Hall officials did not realize that Washington had passed away five years earlier.

Happily for all of us, she is now getting more notice: a historical marker and online recognition from the state of Pennsylvania, a place in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame, enshrinement in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, an episode of WBUR’s Only a Game, an eight-episode BBC podcast on her life, a piece in the Washington Post’s Retropolis series and now an obituary by Juliet Macur in the New York Times “Overlooked” series, which commemorates people who lived remarkable lives beyond that august institution’s gaze.

Washington has long deserved these honors. Her story also illuminates a vibrant world of African American women’s sports, underscoring the creativity, courage and determination of the generations of African Americans who left the rural South and made new lives for themselves in a rapidly changing world.

Washington retired from competition in the 1940s, just as public attention turned to a rising generation of black players who were finally getting the chance to perform on an integrated stage (in her last national championship, the ATA mixed doubles title of 1947, she and partner George Stewart defeated Walter Johnson and an up-and-coming star named Althea Gibson). She lived in Philadelphia until she passed away in 1971. But when interest in segregation-era sports began to revive, and historians began to tell the stories of stars such as Josh Gibson and “Pop” Gates, they found only traces of Washington – a handful of photographs, a list of victories. Even her name got muddled – some time after she died she was mistakenly dubbed Ora Mae, and the old-fashioned, girlish moniker somehow stuck.

When I started to research Washington’s life for Shattering the Glass, I had a handful of sources: a brief description in A.S. “Doc” Young’s 1963 Negro Firsts in Sports, the pioneering work done by Arthur Ashe in A Hard Road to Glory, and some oral history interviews recorded by Rita Liberti as part of a project on black women’s college basketball. None of them said anything about Washington’s early life. But then, a line in an obituary led me to rural Caroline County, Virginia, where a local librarian connected me with one of Washington’s nephews, J. Bernard Childs.

Childs’ eyesight was fading, but his memory was sharp, and he told story after story about his aunt, and about the large, close Washington family – a narrative backed up by data from the U.S. Census.

Ora had been born in Caroline County at the end of the nineteenth century, the fifth of nine Washington children, in an era when the grip of white supremacy was tightening across the South. Times were hard, and one by one the Washingtons left the family farm to seek their fortunes in Philadelphia. Ora’s aunt Mattie was the first to go. A few years later, when teenaged Ora followed, she stayed with her aunt until she found a job as a housekeeper – work she would do all her life.

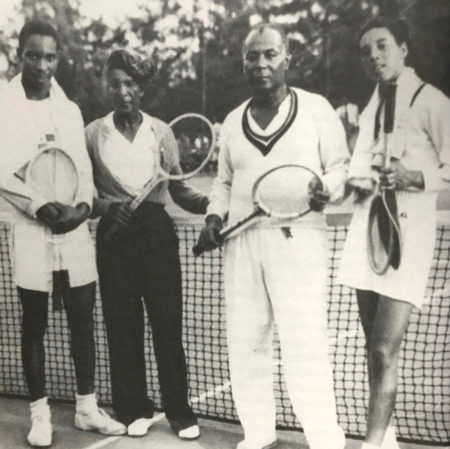

Like many young black working women, she joined the “colored” Germantown YWCA, founded in 1918. She picked up a tennis racket sometime in 1924. Her ability must have shown from the beginning – she won her first national title in 1925, and quickly became the brightest star on the black women’s tennis circuit. Women’s basketball was also gaining popularity, and she took up that sport as well, playing center for the Germantown Hornets before switching to the better-funded Tribunes. The promotional talents of manager Otto Briggs, enthusiastic coverage in the Tribune, and Washington’s star power made the Tribunes into the most celebrated female sports team in the nation.

In 1934, for example, the team traveled to Greensboro, North Carolina, to play the Bennett Belles from Bennett College (unlike most white colleges, many historically black institutions encouraged female students to compete). Briggs booked Greensboro’s spacious city arena, where black teams rarely played, and more than a thousand fans showed up to see what the local paper called “the fastest girls’ team in the world,” paced by “the indomitable, internationally famed and stellar performer, Ora Washington.”

She did not disappoint. Six decades later, when Rita Liberti tracked down several of the Bennett players, they had vivid memories of the Tribunes and of Washington. “She wasn’t a huge person, or very tall,” recalled Ruth Glover Mullen. But she was so fast. So fast and so good.”

“She was intimidating,” added Amaleta Moore. “The way she looked at you: ‘You’ve got no business in my way.’”

When Bennett center Lucille Townsend faced off against Washington at the start of the first game she heard a whispered warning: “Don’t outjump me.” She disregarded the admonition at her peril. “I never saw her when she hit me, but she did it so quick it would knock the breath out of me, and I doubled over,” she explained. “She could hit, and she told me that she had played a set of tennis on her knees and won it.”

Ora Washington needed every ounce of that determination. Like most black female athletes, she navigated multiple worlds. African American tennis was dominated by doctors, lawyers and other professionals who saw the genteel game as evidence of their arrival among a national elite. The working-class crowds who packed the Tribunes’ games were looking for heart-stopping entertainment. The wealthy whites whose homes she made her living cleaning – even a star of her magnitude never made enough from sports to pay the bills – expected deference and discretion. Through it all, it seems quite clear, she stayed true to herself.

Her force of personality shows clearly in one of my favorite stories. She officially retired from tennis singles in 1937, after winning her eighth national title. But in the summer of 1939, she picked up her racket for one last tournament. She reached the finals, defeated rising star Flora Lomax, 6-2, 1-6, 2-6, and promptly retired again. She minced no words about her motives. “Certain people said certain things last year,” she told the Baltimore Afro-American. “They said Ora was not so good any more. I had not planned to enter singles this year, but I just had to go up to Buffalo to prove somebody was wrong. I lost the second set to her but this was the first and only set she ever won from me.”

I suspect that self-assurance contributed to her quick slide from the public eye. Unlike Lomax, a flirtatious beauty who became known as “the glamour girl of tennis,” Washington focused on her play, spoke her mind, and formed her closest relationships with other women. Socializing after games was not her style. “The land at large has never bowed at Ora’s shrine of accomplishment in the proper tempo,” Randy Dixon wrote after her retirement, surmising that “She committed the unpardonable sin of being a plain person with no flair whatever for what folks love to call society.”

But that independence also meant she had a life beyond the court. When her athletic career ended, she slipped into obscurity, but not poverty or despair. She kept working, and spent her time with friends and with her large, extended family. In the summers, when she gathered with family members at the Caroline County farm, she avidly joined the games played on the family croquet court. “She was out there mostly with somebody, about every day,” Childs recalled. “They would go there just about every afternoon.”

Ora Washington’s latest wave of fame thus commemorates not simply athletic talent, but the ability to build a new life from the opportunities at hand. She traveled farther and achieved more than anyone could have imagined for an African American farm girl making her own way at the inauspicious start of the twentieth century. Bringing her back into the public eye not only honors her athletic achievements, it reminds us of the courage and determination that remain to be discovered in so many corners of our nation’s history.

For more about Washington, see “Ora Washington: The First Black Female Athletic Star,” published in David K. Wiggins’ fine edited collection Out of the Shadows: A Biographical History of African American Athletes (University of Arkansas Press, 2006).