No size fits all

CHARLOTTE, NC

The hot pink billboard hovers over a shopping center on the east side of Charlotte, North Carolina. At the center, a young Black woman clad in a short skirt and cropped hoodie lounges on a gilded throne. To her left sits a glittering array of hair care products. To her right, the title proclaims: “From One Queen to Another.”

Angel Reese has come to town.

The LSU hoops star played her way to national renown at the 2023 Women’s Final Four, where her Tigers took the championship game from favored Iowa and the celebrated Caitlin Clark, 102-85. With 30 seconds left in that contest, Reese underscored the achievement by holding her hand between her face and Clark’s in a “can’t see me” gesture pioneered in the World Wrestling Federation. Her lacquered index fingernail marked the spot where her championship ring would rest.

Reese was named the tournament’s most outstanding player, and rose quickly to the top of college sports’ brave new world of Name-Image-Likeness (NIL). As of this November, she was the second-highest NIL earner among college basketball players, beaten only by LeBron James’ son Bronny. She appeared in the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue. She signed contracts with firms that included Coach, Reebok and Mielle, the line of Black hair care products advertised in the Charlotte billboard.

Around the same time the Mielle billboard went up on Sugar Creek, a downtown banner advertising the Iowa-Virginia Tech Ally Tipoff presented Caitlin Clark in a far different light. Clark, whose pinpoint passing and breathtaking 3-point shooting made her college basketball’s 2023 National Player of the Year, stood in the foreground, hair pulled back, no makeup, all business.

Clark’s NCAA run also brought her plenty of NIL success, including contracts with firms such as Nike, Bose, H&R Block and State Farm Insurance. For 2023, her earnings ranked fourth among female basketball players, twelfth overall.

That two such dramatically different women have drawn this kind of widespread acclamation marks a sharp departure from the restrictions faced by previous generations of female athletes. Historically, athletic women have been encouraged – and frequently required – to blunt the “masculine” associations of athletic success by donning skirts, stockings and makeup, speaking in measured tones and downplaying their competitive zeal.

Efforts to fit top athletes into conventional views of decorative femininity showed especially clearly at the AAU national tournament in the middle of the twentieth century. While no Black squad was invited until the late 1950s, the AAU tournament showcased the nation’s best white players and teams, including powerhouses such as Babe Didrikson’s Golden Cyclones, Hazel Walker’s Lewis & Norwood Flyers and the star-studded Hanes Hosiery. Still, organizers felt the need to augment the top-flight play with an annual beauty pageant (won in 1944 by Hanes Hosiery’s Jimmie Vaughn, pictured below).

Anxieties about conventionally feminine appeal persisted into the early 2000s, when promoters of the fledgling WNBA were still seeking to squeeze players into a one-size-fits-all version of feminine charm.

“There was always this question: ‘How are we going to market women’s sport?’” recalled Sue Wicks, who played for the New York Liberty in those early years. “And their answer was, ‘Well, they need dresses and makeup.’” While some players enjoyed dressing up, many did not. “I see some of the pictures, and it’s comical because the players are so awkward,” Wicks continued. “They would never wear that dress, they would never wear lipstick, and you can see they’re just miserable.”

The world of women’s sports and NILs of course remains entangled in cultural conventions and expectations.

Conventional femininity still sells. Angel Reese’s NIL career has been fueled not simply by her remarkable talent, but by her stature as “Bayou Barbie,” a nickname inspired by her willowy figure, flowing hair, and dramatically long nails and lashes. “As the Bayou Barbie, I love to look my best on and off the court!” she gushed in a Mielle press release. “Mielle has always been there for me.”

In contrast, Caitlin Clark’s State Farm debut paired her with the firm’s trademark khakis. The decidedly non-glamorous attire underscored the classic “girl-next-door” image that is part of Clark’s appeal, and which also invokes the mainstream press goodwill that so often comes with being white.

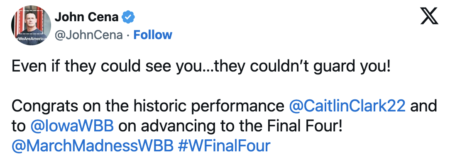

This goodwill showed when Clark threw a “can’t see me” hand after shooting her sixth 3-pointer in Iowa’s Elite Eight victory over Louisville. Reactions were largely positive, including a shoutout from the gesture’s inventor, WWF competitor John Cena.

But when Reese deployed the gesture, social media became a battleground that featured, as sports journalist Dave Zirin put it, “loathsome right-wing men, mostly white, profanely criticizing Reese” as well as “what felt like a coordinated effort from the most wretched corners of the sports commentariat,” involving “people who two weeks ago did not know who Clark was rushing to her defense and attempting to turn her into their latest fragile white martyr—a casualty of the confidence of a Black woman, a confidence that they wanted to break.”

Mainstream condemnation spread so far that even Charles Barkley called Reese’s move “unfortunate,” prompting Zirin to remark: “If Charles Barkley is reaching for the fainting couch, you know that way too many men in the basketball world have lost the plot.”

Reese stood firm, tweeting: “I’m ‘too hood.’ I’m ‘too ghetto.’ I don’t fit the narrative and I’M OK WITH THAT. I’m from Baltimore where you hoop outside & talk trash. . . . Let’s normalize women showing passion for the game instead of it being ‘embarrassing.’”

Clark refused to play the victim, defending Reese and stating: “I’m just lucky enough that I get to play this game and have emotion and wear it on my sleeve. . . . That should never be torn down. That should never be criticized because I believe that’s what makes this game so fun. That’s what draws people to this game. That’s how I’m going to continue to play. That’s how every girl should continue to play.”

In the end, the sagas of these two remarkable competitors say a great deal about present-day American society and culture. They speak to the expanding media landscape that allows athletes to reach out to multiple audiences, to fans of Southern charm, Midwestern chutzpah, urban panache. They show that women can speak out and be heard, a shift underscored by the jump in popularity the WNBA enjoyed after players took leading roles in promoting Black Lives Matter. There’s a long and likely rocky road ahead for these players and their sport, as the spotlight on the women’s game intensifies. But this holiday season we all have much to celebrate.