Judy Rose: persistence pays off

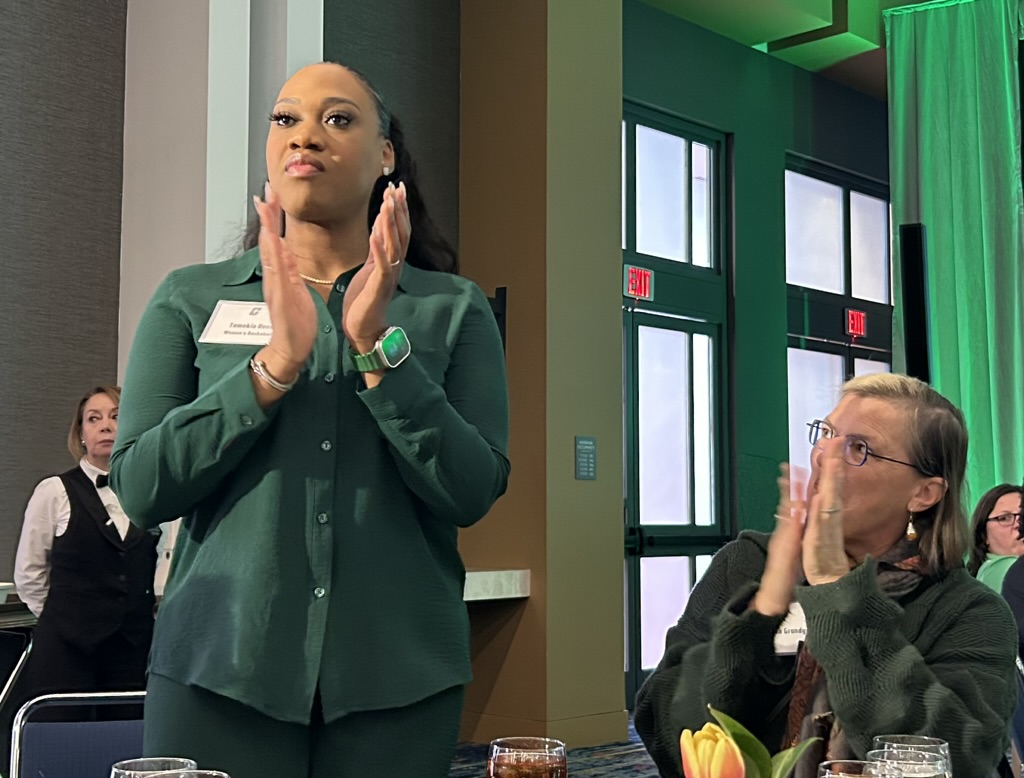

The downtown banquet hall filled with applause as retired UNC Charlotte athletic director Judy Rose stood up from her table and waved to the nearly 300 guests who filled the room.

The occasion was the annual “Let Me Play” luncheon, which Rose had dreamed up twenty years before to raise money for women’s sports at UNC Charlotte. Over two decades, speakers noted, the luncheon had raised several million dollars.

They also reiterated Rose’s many accomplishments during her 43-year tenure at the school. She was one of the first female athletic directors at a Division I school and the first woman to sit on the NCAA’s men’s basketball committee. She oversaw the addition of new teams and the construction of new facilities. She cheered teams on to multiple league titles, and the school was never cited for a major NCAA violation. “She created a way when there was none,” keynote speaker Shelly Cayette-Weston observed.

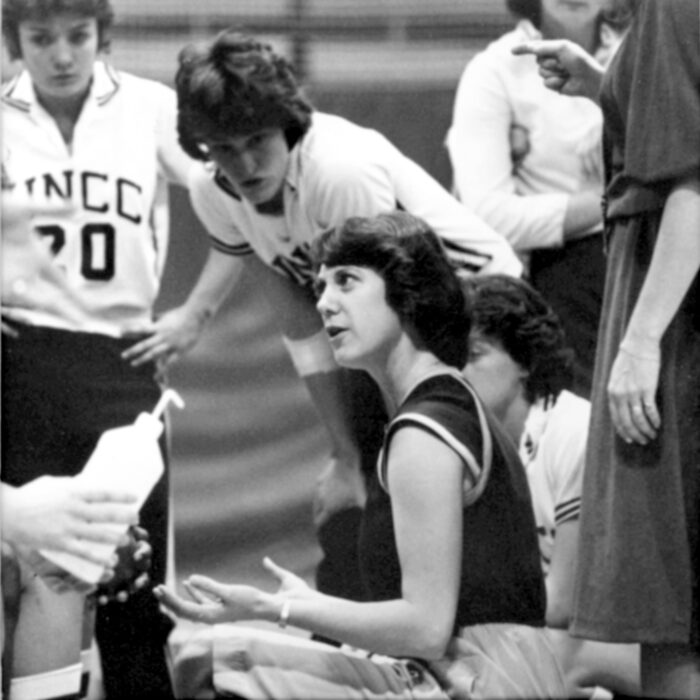

Back in 1975, when Rose was hired to teach physical education and coach several women’s sports, including basketball, the situation did not seem promising. Title IX, the federal legislation that would transform women’s college sports went into effect in 1972. But it would be a long hard road to anything like equality. While Rose and her contemporaries had new opportunities, they often had to build programs from scratch.

As we note in Shattering the Glass, Rose began to study for a master’s in physical education at the University of Tennessee just after the passage of Title IX. It was an auspicious time. The first jobs coaching women’s college teams began as part-time positions, linked to jobs in women’s physical education departments. As a result, most of them went to women.

“There were about thirty of us in grad school at Tennessee, about fifty-fifty male and female,” Rose explained. “And I remember the guys would walk into class – and this is toward the end of the year – and one guy would go: ‘Yes! I am the new junior high football coach at such-and-such junior high school!’ … One of the girls would walk in and she’d go, ‘Guess what, guess what? … I’m the new women’s tennis coach at the University of North Alabama!’ … Now ours was definitely right time, right place.”

But while the jobs were easier to get, they were far more challenging to handle. Most novice male coaches were hired to coach established teams or to assist more experienced coaches. Women, in contrast, had few such mentors.

One of Rose’s classmates, Pat Summitt, fell into the head basketball job at the University of Tennessee when the head coach unexpectedly left. “I was a twenty-two-year-old head coach, and I had four players who were twenty-one,” Summitt later recalled. She dealt with the situation in the best way she knew. “I was hard on them and myself and everyone around me. I thought I had to be. I thought that’s how you commanded respect.”

The first day of practice revealed the flaws in this single-minded approach. “I worked those prospects up and down the court, at full speed, for two solid hours,” she wrote. “At the end of that, I ordered them to run a bunch of conditioning drills. I ran [them] in suicide drill after suicide drill. A group of four young ladies were running together. When they got to the end of the line, they just kept on running. They ran out the door and up the steps, and I never saw them again.”

At least Summitt had players to lose. Rose was not so lucky. Soon after she was hired at UNC Charlotte, she put up signs announcing an organizational meeting for the school’s first women’s basketball team. “I was so excited,” she recalled.

The night of the meeting, few showed up. “I remember I went home to my apartment that night, and I was so depressed,” she explained. One of the women who had hired her “called me at home that night, and she said: ‘How did the meeting go?’ And I said: ‘It was awful.’ And she said: ‘Well, what happened?’ I said: ‘We only had eight people.’ She said: ‘That’s wonderful!’ And I knew I was in trouble.”

Rose met with a similar response when she tried to draw spectators to her games. In one promotional effort, she wrote letters to the city’s high school and junior high girls’ basketball coaches, offering them free tickets to both men’s and women’s games. “I said: ‘If you come to the women’s game, I’ll let you in the men’s game free,’” she explained.

“I kept waiting for the replies,” she said. “I never got a reply, never.” She stayed perplexed until she ran into one of her supporters. “I said: ‘You know I cannot believe that not one person has responded to my letter, not one.’ She said: ‘Who’d you send them to?’ I said: ‘Well, I just addressed it to “Women’s Basketball Coach.”’ … And she said: ‘Uh, Judy, they don’t have women’s basketball in the junior high schools or the high schools in Charlotte.’ I’m like: ‘What?’ There’s nothing to recruit from. So, I mean, it was a rude awakening.”

Still, Rose, Summitt and many other women persisted. Summitt became a coaching legend. Rose built institutions. Across the country, the accomplishments of thousands of women changed the sporting landscape and American society as well.

Cayette-Weston, president of the NBA Charlotte Hornets’ business operations, inspired the crowd with her description of how sports built her confidence, teamwork and time-management skills as a basketball player at Tulane. “It made me a better version of myself,” she said. “Every investment in women’s sports is an investment in moving our society forward.”

Players and coaches were scattered around the tables, including UNC Charlotte’s newly hired women’s basketball coach, Tomekia Reed, who came to Charlotte with several years of coaching success at other schools. The confidence she and many others showed was palpable.

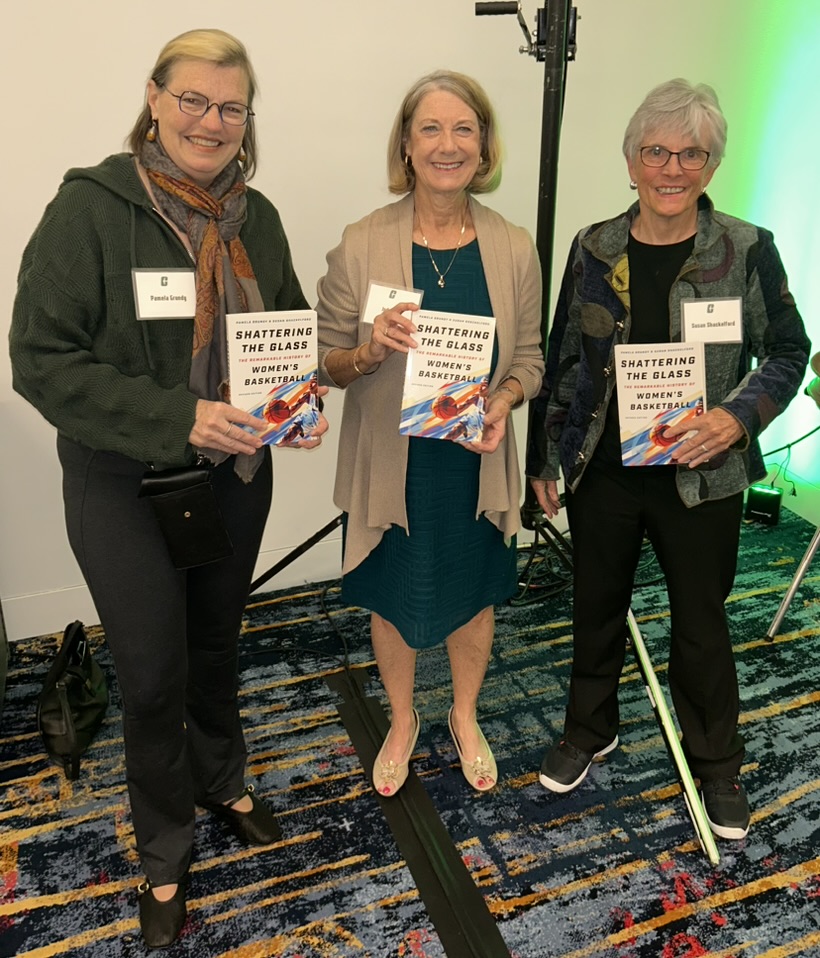

We’ve admired Judy Rose for years – we were both at the first Let Me Play luncheon, just after the first edition of Shattering the Glass was published. It was marvelous to sit among so many of her supporters and see the grand results of all her work and dedication. Plus she’s a fan of Shattering the Glass. Can’t get much better than that.