CHARLOTTE, NC

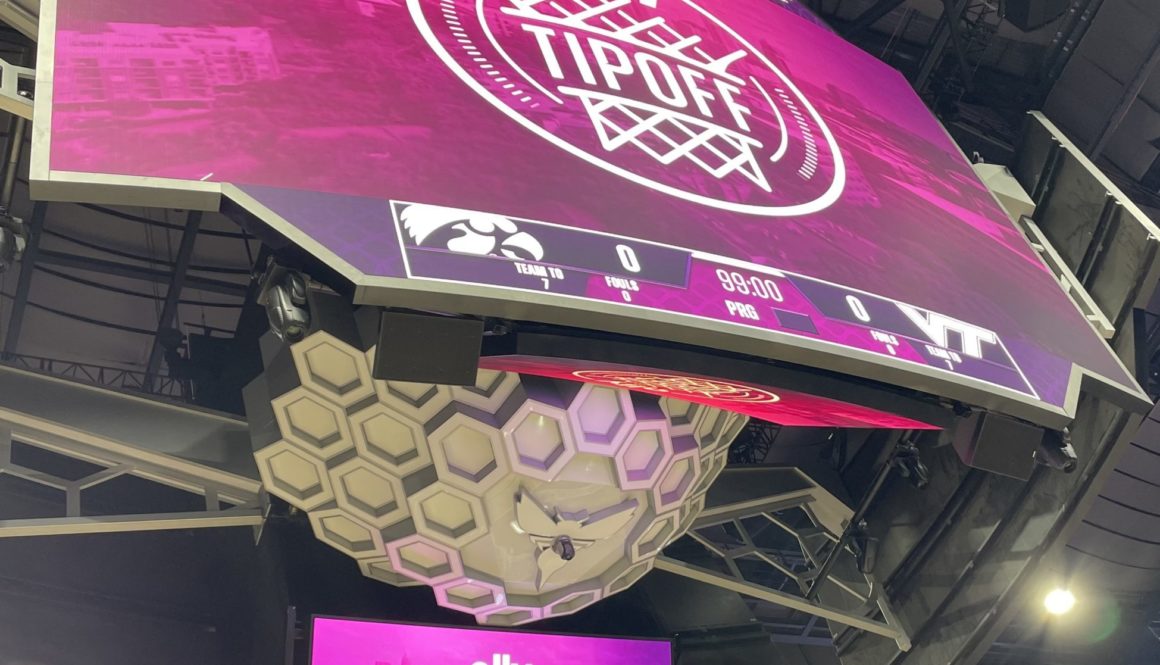

The inaugural Ally Tipoff has reached its final minute and the crowd of 15,000 has risen to its feet. The third-ranked Iowa Hawkeyes, captained by the incandescent Caitlin Clark, have been trading three-pointers with the eighth-ranked Virginia Tech Hokies. The lead has changed hands 11 times throughout the game. With 31 seconds left and the Hawkeyes leading 76-71, the teams break for a timeout.

There hasn’t been a scene like this in Charlotte since 1996, when the city hosted the Women’s Final Four. That year, the Tennessee Lady Volunteers, featuring freshman standout Chamique Holdsclaw and Charlotte native Tiffani Johnson, claimed the national title with an overtime win over the defending champion UConn Huskies in the semis, and then with a dominating victory over the Georgia Lady Bulldogs, 86-65.

Back in 1996, fans of women’s basketball evisioned a grand future. That year, a star-studded Olympic team dazzled crowds at exhibition games throughout the country, then took the gold medal in Atlanta. Not one but two professional leagues emerged from the excitement: the independent American Basketball League and the NBA-sponsored Women’s National Basketball Association. (Charlotte got one of the original WNBA teams, the Charlotte Sting, paced by University of Virginia phenom Dawn Staley).

A fierce rivalry between Tennessee, coached by Pat Summitt, and the University of Connecticut, coached by Geno Auriemma, energized the college game. Play constantly improved, driven by stars like UConn’s Diana Taurasi, LSU’s Seimone Augustus, and Tennessee’s Candace Parker. We completed the first edition of Shattering the Glass amid that optimism, hoping the sport would continue to expand.

But then momentum slowed. The ABL had lasted only two years. While the NBA’s deep pockets kept the WNBA afloat, many teams struggled. The league averaged nearly 11,000 spectators per game in 1998, but only 8,500 in 2004. The Cleveland Rockers folded in 2003, the Charlotte Sting in 2007 and the Houston Comets, which had won the first four WNBA championships, in 2008.

The mismatch between improving play and stagnant audiences made it clear that the main challenges lay beyond the game itself. In 2008 the Seattle Storm was purchased by Force 10 Hoops LLC, a group of Seattle women led by Dawn Trudeau and including Lisa Brummel, Ginny Gilder and Anne Levinson. Gilder started attending league meetings, where then-NBA-commissioner David Stern focused on ticket sales. “At that point, he would just rail on everybody,” she explained in a recent interview. “‘You’ve got to sell, you’ve got to sell, you’ve got to sell.’ “I don’t think he ever really understood how much bias there was against women.”

Those biases ran deep. Men’s sports drew on many lines of support, including media exposure and corporate sponsorship. These key arenas were largely run by men, and each presented its own challenges.

Although Seattle was considered a progressive city, it was tough to build corporate support for a women’s team – even a high-performing squad such as the Storm, which had won the WNBA championship in 2004 and would win again in 2010. When Force 10 Hoops bought the team, longtime fan Peggy Haslach, whose financial firm often worked with NCAA teams, approached Gilder about taking on the Storm’s financial planning. Gilder made it clear that the Storm would give priority to firms that were willing to become team sponsors.

“I came back and I went to my boss and I said, ‘The Storm is willing to work with us, but here’s the deal, it’s pay to play,'” Haslach recently recalled. “‘So you have to sponsor the team.’ And he looked at me and he goes, ‘You know, Peggy, I have to do this only for those sports that I feel the whole firm can get into.'”

“And the thing was, the games were accessible,” Haslach noted. “They were inexpensive. And not only that, women were much better behaved on the basketball court than the guys. It was a family situation. So I learned quickly that they really didn’t want to have anything to do with it.”

But now, 15 years later, circumstances seem more promising. For one, women have more corporate decision-making power. Many of today’s female executives played sports in high school and college, and some have reached the point where they can direct company resources towards the games that meant so much to them.

Ally Financial, the main sponsor of the Tipoff game, has become one of the leaders of this effort. Andrea Brimmer, a standout soccer player who became a top-performing advertising executive, put together a team of “badass” women that included former Yale basketball player Stephanie Marciano (seen with us below), former Michigan State softballer Bridget Sponsky and former UNC Chapel Hill track athlete Jackie Hartzell, who attended Hopewell High right here in Mecklenburg County. In 2022, the 50th anniversary of Title IX, Ally pledged to start splitting the company’s sports promotion dollars 50-50 between men’s and women’s sports.

The bank also put its clout to use in broadcast negotiations.

Ally became a top sponsor of the National Women’s Soccer League in 2021 and a year later drove the effort to move the league’s championship game into a primetime TV spot, putting up extra money to make it happen. In 2023, NWSL commissioner Jessica Berman negotiated a rights deal for an impressive $240 million and was resolute in what the rights required. “Jessica, in the NWSL broadcast negotiations was, ‘It’s got to be a game of the week,” Brimmer explained. “’It’s got to be prime time. We’ve got to have a prime time championship. It’s requisite as part of the deal.’”

The Tipoff was dreamed up by Charlotte Sports Foundation executive director Danny Morrison, who was dazzled by Caitlin Clark’s performance at the 2023 Final Four and wanted her to play in Charlotte. Ally, which had a major presence in the banking-focused city, was an obvious partner. Morrison asked, and got a yes almost immediately.

The Tipoff’s promotion team resolved to shine the brightest possible spotlight on the game. Morrison, whose career included a stint as president of the Carolina Panthers, knew what it would mean to orchestrate a top-level event – one as far removed as possible from the sad situation at the 2021 NCAA tournament, which exposed the glaring inequities between men and women’s college ball.

The players were treated with style, from the state-of-the-art court to the top-quality locker rooms to the banners that greeted them as they headed to the court. Off-court attention was so enthusiastic that Clark reportedly had to hide beneath a hoodie when she ventured out onto the Charlotte streets.

The teams responded with a terrific game. They showed some early-season rust – neither team shot well in the first half. But as the halftime buzzer sounded, Virginia Tech’s Georgia Amoore hit a swisher from half court to pull the Hokies within one point – 33-32. After a slow shooting start, Clark drove repeatedly to the basket, drew 16 fouls and ended with 44 points to Amoore’s 31. The final score was Iowa 80, Virginia Tech 76.

At the postgame press conference, coaches and players raved about their experience. We asked Clark how she saw this moment in women’s sports history, and her response took social media by storm, as well as being featured prominently in the national press.

“Crowds like this should become normal for women’s basketball,” she said. “Iowa has a great history in Title IX, and making it important. I grew up a fan of women’s basketball, and I’ve always understood there’s really great players in this game who are really fun to watch. At the same time, they’re some of my biggest role models, and to see myself on this stage now, it’s very hard to wrap my hands around the environments we get to play in.”

It was a joy to experience such a standout event.

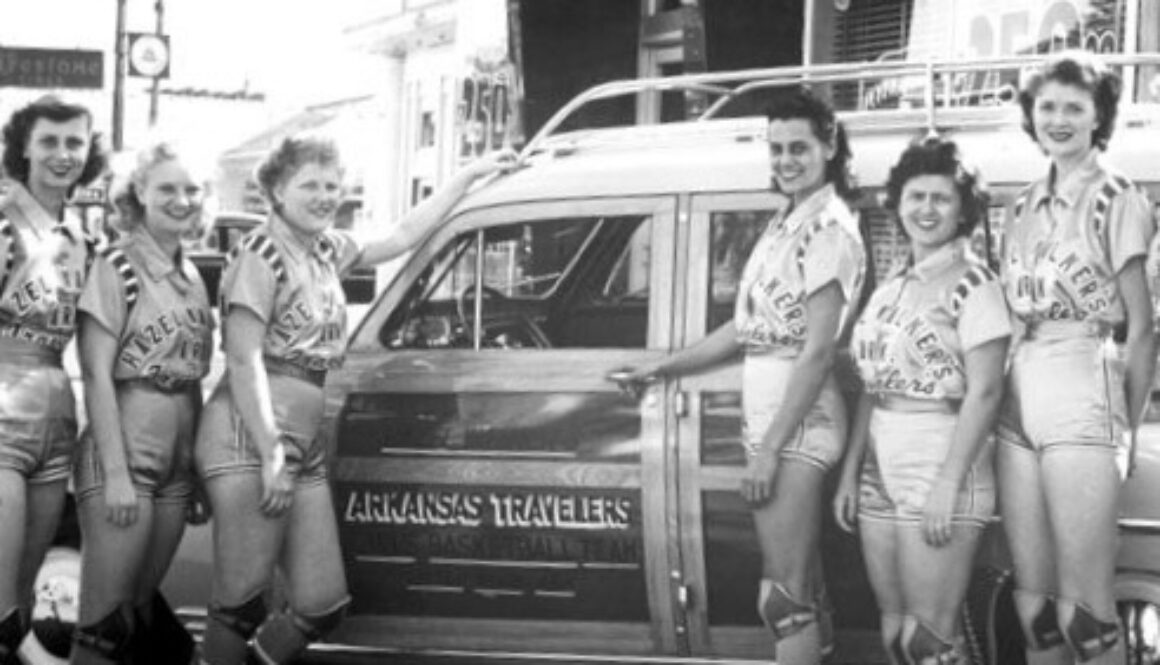

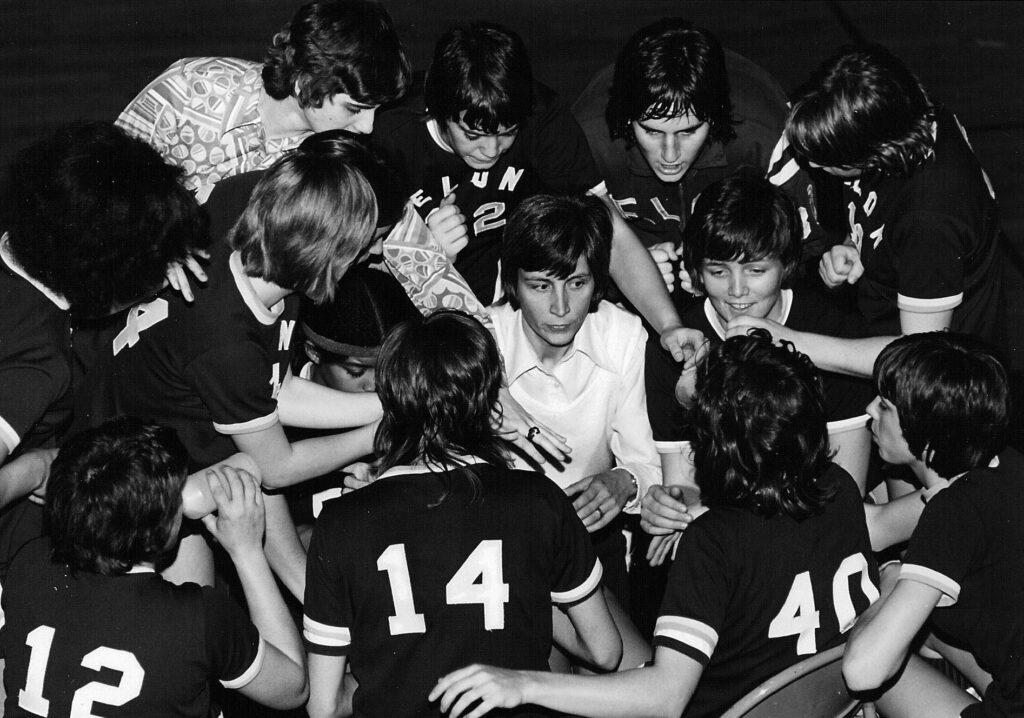

Our work on Shattering has taught us not to take such moments for granted. American women’s sports has a history of ups and downs. At the end of the 19th century, student excitement over intercollegiate competition was diverted into intramurals and physical education. The vibrant competition that took shape in high schools during the 1930s and 1940s was largely squelched in the conservative Cold War era. Then came the post-1996 stagnation.

But at the moment, from where we sit, things look pretty good.

Note: The photo of the 1996 Olympic team is courtesy of USA Basketball and the photo of the Ally banner is courtesy of the Charlotte Sports Foundation. We took all the others.