What she wore

DALLAS, TEXAS

Angel Reese’s left leg flashes royal purple as she glides across the court, sporting a single-leg athletic “sleeve.”

In a recent talk with The Sporting News, Reece explained she wears the covering in part to hide a surgical scar, and in part as a nod to WNBA stars A’ja Wilson and T’ea Cooper, who pioneered the popular look within their league.

Although she did not mention it, for many more “mature” basketball fans, the outfit also invokes the glamor of sprinter Florence Griffith-Joyner, whose flowing hair, elaborately painted nails and stylish, one-legged running suits transformed the image of female track stars in the 1980s.

As long as American women have played sports, their appearance has been closely examined for clues about their relationship to prevailing feminine ideals – ideals that the assertive clashes of competitive sports have often challenged. Some of this century-long interplay among clothes, players, and changing social norms can be found in Bloomers and Beyond, an article I published in Southern Cultures in the fall of 1997. It’s a fun read – I recommend it.

As long as American women have played sports, their appearance has been closely examined for clues about their relationship to prevailing feminine ideals – ideals that the assertive clashes of competitive sports have often challenged. Some of this century-long interplay among clothes, players, and changing social norms can be found in Bloomers and Beyond, an article I published in Southern Cultures in the fall of 1997. It’s a fun read – I recommend it.

The present-day is no different. But in a departure from much of women’s basketball history, the uniforms worn by college players at the Final Four and elsewhere have not been deliberately designed to address questions of femininity.

Not that the NCAA doesn’t regulate what college athletes wear. On any imaginable subject, the specifics in the NCAA rules books boggle the mind. To take just one example, in the 2022-23 women’s basketball book Section 16, Article 1 decrees: “The ball shall be spherical. Spherical shall be defined as a round body whose surface at all points is equidistant from the center, except at the approved black rubber ribs (channels and/or seams).”

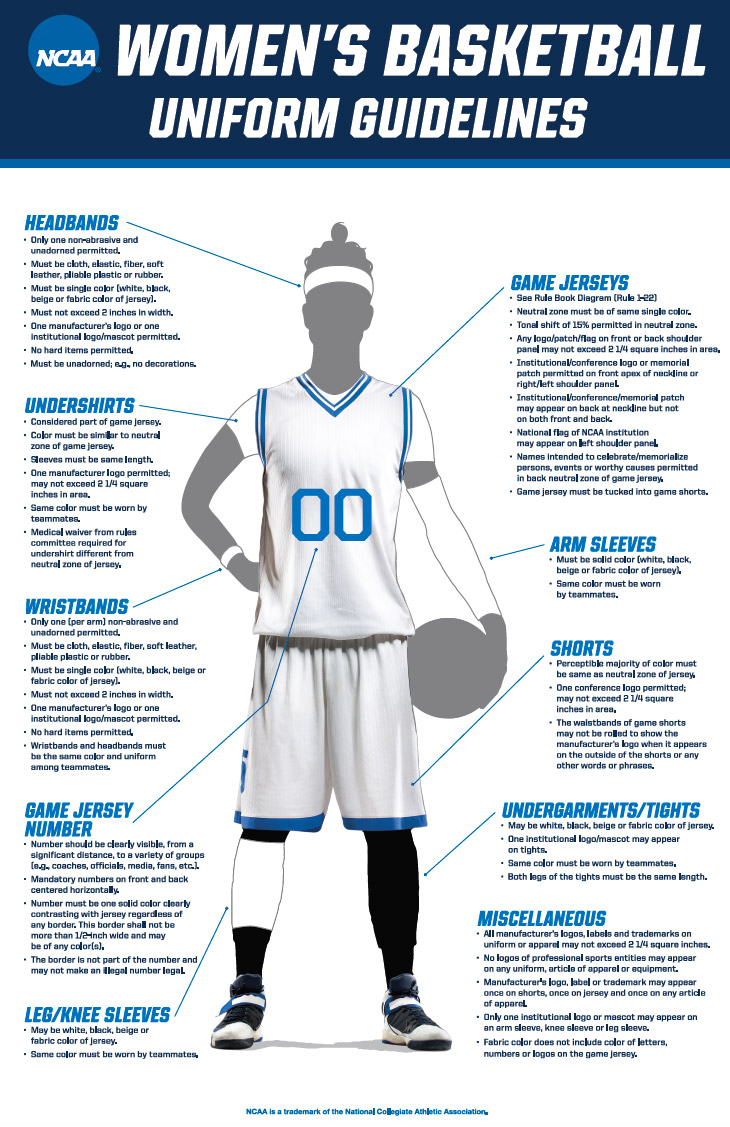

Uniform requirements display similar detail. They regulate colors, the size, number, and placement of school and manufacturer logos, and the design of sleeves, headbands and socks. They designate a “neutral zone” on jerseys within which “commercial names, logos, marks, and slogans are prohibited.” There is some leeway regarding color: “a tonal design effect is permitted within the neutral zone(s) provided the tonal shifts are not more than 15 percent from the color of the neutral zone.” Players must tuck in their shirts.

Uniform requirements display similar detail. They regulate colors, the size, number, and placement of school and manufacturer logos, and the design of sleeves, headbands and socks. They designate a “neutral zone” on jerseys within which “commercial names, logos, marks, and slogans are prohibited.” There is some leeway regarding color: “a tonal design effect is permitted within the neutral zone(s) provided the tonal shifts are not more than 15 percent from the color of the neutral zone.” Players must tuck in their shirts.

The regulations fill five and a half pages of the NCAA women’s basketball rules book as well as six pages of a separately issued “Supplemental Apparel Guide,” which includes instructions such as “Institutional names, mascots or logos are permitted on the game shorts. There is no limit to the number of these permissible logos on the game shorts, but these count toward the color of the shorts.”

Despite their Byzantine appearance, the regulations embody a fairly straightforward set of priorities – helping coaches and referees identify players, tamping down commercial entanglements, and in the words of the supplemental guide, regulating “IMAGE – How players appear on television/fan appeal” (this seems to reference the tucked-in shirt requirement).

Unlike the guidelines laid out by North Carolina officials in 1921, which declared that the state’s female high school players “should be dressed in clothing which is not only proper but attractive, and which will remain in place during the game,” NCAA rules are essentially identical for men and women.

Such developments do not mean that college basketball games unfold in a gender “neutral zone.” Rather, it is left up to coaches and players to chart their own paths, using tools such as hairdos, makeup, and the outfits worn by coaches on the sidelines. And although female athletes have more leeway than ever regarding self-presentation, the greatest social media followings, and the highest NIL payments tend to go to those women who fashion images that mesh well with persisting ideals about glamorous femininity.

The dramatic success of players such as Reese, who has filed to trademark the nickname “Bayou Barbie,” or NIL stars Haley and Hanna Cavinder make clear that while some things have changed, some remain very much the same.